Author's details

- Dr. Adekanye Temitope Victor

- MBBS, Senior Registrar, Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department, Lagos University Teaching Hospital. Nigeria

- (Lagos), Senior Registrar, Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department, Lagos University Teaching Hospital. Nigeria

Reviewer's details

- Dr Okoro Austin Chigozie

- MBBS, MWACS, MPH, FWACS

- Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. Evercare Hospital. Lekki. Nigeria

- Date Uploaded: 2024-10-10

- Date Updated: 2025-02-06

Tumours of the Cervix Uteri

Summary

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide and the leading cause of cancer death among women in sub-Saharan Africa. 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths of cervical cancer were reported in 2020. There is a disproportionate effect on low- and middle-income countries as they account for over 80% of the global CC burden (1). Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest age-standardized incidence and mortality rates in 2018(2). Co-factors and include; STIs (HIV chlamydia infections), young age at first pregnancy, smoking, long use of oral contraceptives, early sexual exposure, multiple sexual partners and high parity contribute to the higher incidence in Africa. CC ranks as the 2nd most common cancer among women between 15 and 44 years of age in Nigeria.

HPV is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact, including during oral sex, hand-to-genital contact, and sexual intercourse. Risk factors for HPV and cervical cancer include young age at sexual debut, multiple sexual partners, high parity, smoking, herpes simplex, HIV, coinfection with other genital infections, and prolonged use of oral contraceptive pills. HPVs are small icosahedral viruses, approximately 50 to 60 nm in diameter, non-enveloped, containing a circular double-stranded DNA genome (between 7000 and 8000 bp), infecting mucosal and skin epithelia in a specific manner and inducing cell proliferation (5). HPV DNA, the oncoproteins E6 and E7 interfere with the critical host cell cycle; specifically, E6 interferes with suppressive tumour protein p53, whereas E7 interferes with retinoblastoma protein (pRB) (6).

Patients with cervical cancer are maybe asymptomatic during the early stages. With the subsequent progression of the disease, symptoms like abnormal vaginal bleeding (especially between periods, after menopause or following sexual intercourse), vaginal discomfort, pain during intercourse, persistent pain in the back, legs, or pelvis, weight loss, fatigue and loss of appetite, swelling in the legs. malodorous vaginal discharge and dysuria become more prominent. In the late stages, urinary or faecal incontinence may occur in cases of a fistulous connection between the tumour and the bladder or between the tumour and the rectum.

A complete medical history must include a sexual history, including the patient's age at first sexual intercourse. Sexual history also contains questions about postcoital bleeding and pain during intercourse. Questions about previous STIs, including HPV and HIV, the number of lifetime sexual partners, tobacco use, and prior vaccination against HPV are all vitally important. Women should also be asked about menstrual patterns, abnormal bleeding, persistent vaginal discharges, irritations, and known cervical lesions (7).

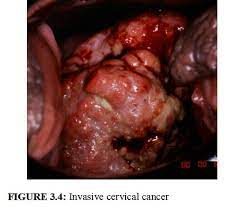

The physical exam must include a complete evaluation of the external and internal genitalia. Positive exam findings in women with cervical cancer might include a friable cervix, visible cervical lesions, erosions, masses, bleeding with the examination, and fixed adnexa. An examination under anaesthesia can give a better insight into the stage of cervical cancer.

Differential diagnoses of cervical cancer include

- Cervicitis

- Cervical polyps

- Cervical fibroids

- Endometrial cancer

- Vaginitis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Packed cell volume and complete blood count (evaluates the extent of blood loss from vaginal bleeding episodes) to detect anaemia.

- Electrolyte, urea and creatinine (detects renal function impairment)

- Abdominopelvic ultrasound scan (first-line imaging to detect the tumour)

- Cystoscopy (visualizes tumour spread to bladder mucosa)

- Proctoscopy (visualizes tumour spread to rectum)

- Chest x-ray (detects metastasis to lungs)

- Intravenous urography (detects ureteric occlusion in stage 3 disease)

- Abdominopelvic CT scan/MRI/PET scan (excellent for detecting local tumour extension, and staging and can also be used for monitoring tumour response.

Stage I

The disease is strictly confined to the cervix, with the A/B designation indicating the depth of invasion (≤5 3 or >5 mm).

Stage II

The disease invades beyond the uterus but has not extended into the lower vagina or to the pelvic side wall

This stage also has an A/B designation based on the greatest dimension (with 4cm cut-off) and involvement of the parametria

Stage III

The disease has extended to the lower one-third of the vagina (11IA) or the pelvic side wall and/or hydronephrosis/non-functioning kidney (I11B), and/or pelvic/paraaortic lymphadenopathy (111C).

Stage IVA

The disease is locally aggressive, involving adjacent organs such as the bladder or rectum.

Stage IVB

The disease has spread to other solid distant organs; this stage can also be indicative of nonregional nodal disease (8).

The treatment of cervical cancer starts from prevention which could be primary (screening for detection and treatment of pre-neoplastic lesions); secondary (treatment of pre-neoplastic lesions, early cervical carcinoma and prevention of complications); tertiary (treatment of late or advanced cervical carcinoma and complications); palliative care (for advanced lesions and end of life care).

Diagnoses involves examination under anaesthesia to stage, obtain a biopsy for pathological diagnosis (confirmatory) and prognosticate as well as formulate treatment plan. The staging is aided by imaging studies.

Treatment of early-stage disease is usually surgical resection, ranging from a conization to a modified radical hysterectomy. Conization or trachelectomy may be an option for women with early-stage disease who desire future fertility. Advanced cases are usually managed initially with chemoradiation followed by (+/-) surgery. However, women with a high risk of residual tumour postresection or suboptimal surgery, may require adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy and radiation.

Prognostic factors for survival include disease stage, lymph node involvement, tumour volume, lympho-vascular space invasion, and histological type and grade of tumour. Routine follow-up visits are recommended every 3–4 months for the first 2–3 years, then every 6 months until 5 years,

and then annually for life. At each visit, history taking and clinical examination are carried out to detect treatment complications and psychosexual morbidity, as well as assess for recurrent disease. When diagnosed early, the 5-year relative survival rate for cervical cancer is approximately 92%. This value drops to 60% when diagnosis is made after spread to local or regional lymph nodes and 19% with distant metastasis at diagnosis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for a global initiative for the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem by implementing the following 90%–70%–90% triple pillar intervention strategy before the year 2030:

- 90% of girls to be fully vaccinated with two doses of HPV vaccine by the age of 15 years;

- 70% of women screened using a high‐performance screening test at the age of 35 and 45 years; and

- 90% of women to be detected with cervical lesions to receive treatment and care (9).

Cervical cancer remains a significant public health challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, where limited access to screening and vaccination programs contributes to high incidence and mortality rates. Early detection through regular screening and the introduction of HPV vaccination are critical in reducing the disease burden. Improving healthcare infrastructure, awareness, and access to preventive measures is essential to address the disparities and improve outcomes for women affected by cervical cancer in the region.

Miss I.J, a 43-year-old P2+3(1A) presented to the gynaecology clinic of LUTH 1 year ago with a 3-month history of recurrent bleeding per vaginam following intercourse and a 2-week history of passage of foul-smelling vaginal discharge in between episodes of bleeding. She was single, has had multiple sexual partners (about 10) and her sexual debut was at 13 years of age. She was also HIV-positive and has not had any HPV vaccinations or screening done in the past. On examination, she was pale, and her vital signs were within normal limits. There was no significant finding on abdominal examination, but pelvic examination revealed a cervical mass with spread to the upper 2/3rd of vagina and pelvic side wall making her at least stage 3b. An examination under anaesthesia and biopsy was done for her and the histology result showed she had a non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. She was managed subsequently by radio-oncologists.

- Habtemariam LW, Zewde ET, Simegn GL. Cervix Type and Cervical Cancer Classification System Using Deep Learning Techniques. Medical Devices: Evidence and Research. 2022;15.

- Yang L, Boily MC, Rönn MM, Obiri-Yeboah D, Morhason-Bello I, Meda N, et al. Regional and country-level trends in cervical cancer screening coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic analysis of population-based surveys (2000–2020). PLoS Med. 2023;20(1).

- Manini I, Montomoli E. Epidemiology and prevention of Human Papillomavirus. Ann Ig. 2018;30(4).

- Rosendo-Chalma P, Antonio-Véjar V, Ortiz Tejedor JG, Ortiz Segarra J, Vega Crespo B, Bigoni-Ordóñez GD. The Hallmarks of Cervical Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms Induced by Human Papillomavirus. Biology. 2024; 13(2):77.

- Ghosh I, Mandal R, Kundu P, Biswas J. Association of genital infections other than human papillomavirus with pre-invasive and invasive cervical Neoplasia. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2016;10(2).

- Romero-Masters JC, Lambert PF, Munger K. Molecular Mechanisms of MmuPV1 E6 and E7 and Implications for Human Disease. Vol. 14, Viruses. 2022.

- Hutchcraft ML, Miller RW. Bleeding from Gynecologic Malignancies. Vol. 49, Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2022.

- Salib MY, Russell JHB, Stewart VR, Sudderuddin SA, Barwick TD, Rockall AG, et al. 2018 Figo staging classification for cervical cancer: Added benefits of imaging. Radiographics. 2020;40(6).

- Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2021;155(S1).

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Tumours of the Cervix Uteri

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide and the leading cause of cancer death among women in sub-Saharan Africa. 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths of cervical cancer were reported in 2020. There is a disproportionate effect on low- and middle-income countries as they account for over 80% of the global CC burden (1). Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest age-standardized incidence and mortality rates in 2018(2). Co-factors and include; STIs (HIV chlamydia infections), young age at first pregnancy, smoking, long use of oral contraceptives, early sexual exposure, multiple sexual partners and high parity contribute to the higher incidence in Africa. CC ranks as the 2nd most common cancer among women between 15 and 44 years of age in Nigeria.

- Habtemariam LW, Zewde ET, Simegn GL. Cervix Type and Cervical Cancer Classification System Using Deep Learning Techniques. Medical Devices: Evidence and Research. 2022;15.

- Yang L, Boily MC, Rönn MM, Obiri-Yeboah D, Morhason-Bello I, Meda N, et al. Regional and country-level trends in cervical cancer screening coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic analysis of population-based surveys (2000–2020). PLoS Med. 2023;20(1).

- Manini I, Montomoli E. Epidemiology and prevention of Human Papillomavirus. Ann Ig. 2018;30(4).

- Rosendo-Chalma P, Antonio-Véjar V, Ortiz Tejedor JG, Ortiz Segarra J, Vega Crespo B, Bigoni-Ordóñez GD. The Hallmarks of Cervical Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms Induced by Human Papillomavirus. Biology. 2024; 13(2):77.

- Ghosh I, Mandal R, Kundu P, Biswas J. Association of genital infections other than human papillomavirus with pre-invasive and invasive cervical Neoplasia. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2016;10(2).

- Romero-Masters JC, Lambert PF, Munger K. Molecular Mechanisms of MmuPV1 E6 and E7 and Implications for Human Disease. Vol. 14, Viruses. 2022.

- Hutchcraft ML, Miller RW. Bleeding from Gynecologic Malignancies. Vol. 49, Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2022.

- Salib MY, Russell JHB, Stewart VR, Sudderuddin SA, Barwick TD, Rockall AG, et al. 2018 Figo staging classification for cervical cancer: Added benefits of imaging. Radiographics. 2020;40(6).

- Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2021;155(S1).

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Tumours of the Cervix Uteri

Background

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide and the leading cause of cancer death among women in sub-Saharan Africa. 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths of cervical cancer were reported in 2020. There is a disproportionate effect on low- and middle-income countries as they account for over 80% of the global CC burden (1). Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest age-standardized incidence and mortality rates in 2018(2). Co-factors and include; STIs (HIV chlamydia infections), young age at first pregnancy, smoking, long use of oral contraceptives, early sexual exposure, multiple sexual partners and high parity contribute to the higher incidence in Africa. CC ranks as the 2nd most common cancer among women between 15 and 44 years of age in Nigeria.

Further readings

- Habtemariam LW, Zewde ET, Simegn GL. Cervix Type and Cervical Cancer Classification System Using Deep Learning Techniques. Medical Devices: Evidence and Research. 2022;15.

- Yang L, Boily MC, Rönn MM, Obiri-Yeboah D, Morhason-Bello I, Meda N, et al. Regional and country-level trends in cervical cancer screening coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic analysis of population-based surveys (2000–2020). PLoS Med. 2023;20(1).

- Manini I, Montomoli E. Epidemiology and prevention of Human Papillomavirus. Ann Ig. 2018;30(4).

- Rosendo-Chalma P, Antonio-Véjar V, Ortiz Tejedor JG, Ortiz Segarra J, Vega Crespo B, Bigoni-Ordóñez GD. The Hallmarks of Cervical Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms Induced by Human Papillomavirus. Biology. 2024; 13(2):77.

- Ghosh I, Mandal R, Kundu P, Biswas J. Association of genital infections other than human papillomavirus with pre-invasive and invasive cervical Neoplasia. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2016;10(2).

- Romero-Masters JC, Lambert PF, Munger K. Molecular Mechanisms of MmuPV1 E6 and E7 and Implications for Human Disease. Vol. 14, Viruses. 2022.

- Hutchcraft ML, Miller RW. Bleeding from Gynecologic Malignancies. Vol. 49, Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2022.

- Salib MY, Russell JHB, Stewart VR, Sudderuddin SA, Barwick TD, Rockall AG, et al. 2018 Figo staging classification for cervical cancer: Added benefits of imaging. Radiographics. 2020;40(6).

- Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2021;155(S1).

Advertisement