Author's details

- Abdulgafar Lekan Olawumi

- MBBS, MHE, MPH, FWACP, FMCFM

- Department of Family Medicine, Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital Kano, Nigeria

Reviewer's details

- Dr. Gboyega Olarinoye

- MBBS, FMCP.

- Dermatologist FMC Keffi Nassarawa State. Nigeria

- Date Uploaded: 2025-05-15

- Date Updated: 2025-12-22

Scabies

Key Messages

- Scabies is a highly contagious mite infestation associated with overcrowding and close contact, not poor hygiene.

- It causes intense nocturnal itching and characteristic burrows, with severe forms in infants and immuno-compromised individuals.

- Diagnosis is mainly clinical in low-resource settings, supported by simple bedside tests when available.

- Effective control requires simultaneous treatment of patients and close contacts, plus strict hygiene measures.

- Early treatment prevents complications, stigma, and ongoing community transmission.

Scabies is a highly contagious skin condition caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. It is one of the major neglected tropical diseases which affect individuals of all ages, genders, ethnic backgrounds, and socioeconomic statuses. However, it is primarily associated with overcrowded living conditions and poverty rather than poor personal hygiene. Scabies has a global distribution, with an estimated 300 million cases reported annually. The disease is endemic in many developing countries, where limited access to healthcare and sanitation contributes to its persistence. In developed nations, scabies tends to occur in institutional outbreaks, particularly in hospitals, nursing homes, and long-term care facilities, where close contact among individuals facilitates its rapid spread.3 Despite its prevalence, scabies remain highly treatable with appropriate medical intervention and improved living conditions.

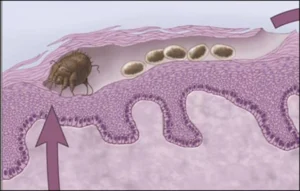

The pathophysiology of scabies begins when the female Sarcoptes scabiei mite burrows into the stratum corneum of the skin, laying eggs and depositing fecal material. Within 3–4 days, the eggs hatch into larvae, which mature into adult mites within two weeks, continuing the infestation cycle. The mites trigger an intense immune response, primarily due to their secretions, eggs, and excreta, leading to itching (pruritus) and skin inflammation.5 The hallmark symptom, severe nocturnal itching, results from a delayed Type IV hypersensitivity reaction to mite antigens, developing 2–6 weeks after initial exposure. In recurrent infections, symptoms appear within 1–4 days due to prior sensitization. The skin lesions, including papules, burrows, and excoriations, occur mainly in warm, intertriginous areas like the finger webs, wrists, axillae, and genital region. In crusted (Norwegian) scabies, seen in immunocompromised individuals, the mite burden is extremely high, leading to widespread hyperkeratotic plaques and severe skin scaling.

Figure 1: A sketch and picture showing scabies mite burrows in the stratum corneum of the skin.

Scabies affects over 200 million people worldwide, with prevalence ranging from 0.2% to 71.4%. High rates have been reported in schools, including 31% in Malaysia, 33% in Turkey, 87.3% in Thailand, and 61–62% in Bangladesh.In Africa, prevalence remains persistently high, with studies showing 4% in Mali, 0.7% in Malawi, 8.3% in Kenya, 5.2% in Guinea-Bissau, 15.9% in Gambia, 2.9–65% in Nigeria, and 2.5–78.4% in Ethiopia, reflecting significant regional variations.

Scabies present differently across age groups but are universally marked by intense nocturnal itching and skin lesions. In infants and young children, lesions often appear on the face, scalp, palms, and soles, sometimes mimicking eczema or impetigo. Older children and adolescents typically develop lesions in the finger webs, wrists, axillae, and genital region, with a higher risk of secondary bacterial infections. Adults commonly experience scabies in the hands, wrists, elbows, and groin, with women often affected around the breasts and men in the scrotal region. In elderly and immunocompromised individuals, crusted (Norwegian) scabies may develop, featuring thick, scaly plaques with minimal itching, making them highly contagious. The lesions can involve the scalp, hands, feet, and nails, resembling psoriasis. Early detection and treatment are crucial to prevent complications and transmission, especially in vulnerable populations.

In resource-limited settings, clinical diagnosis remains the primary method due to limited access to advanced diagnostic tools. The following approaches are commonly used:

- Clinical Examination: Diagnosis is based on intense nocturnal itching, burrows, and characteristic lesions in warm areas (finger webs, axillae, waist, genitals). A history of close contact with affected individuals supports the diagnosis.

- Dermoscopy: A handheld dermatoscope can detect Sarcoptes scabiei mites, eggs, or fecal matter (scybala) in burrows, though it is not widely accessible in Nigeria.

- Burrow Ink Test (BIT) – Applying ink over suspected burrows and wiping it off can highlight tunnel-like markings, aiding visual confirmation.

- Adhesive Tape Test – Transparent tape is pressed onto affected skin, removed, and examined under a microscope for mites and eggs.

Several skin conditions can mimic scabies due to similar itching and rash patterns:

- Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema) – Chronic, itchy, and inflamed skin, often affecting flexural areas, without burrows or nocturnal worsening of pruritus.

- Contact Dermatitis – Localized rash due to irritants/allergens, typically with clear borders and no burrows.

- Psoriasis – Well-demarcated, scaly plaques, often on the elbows, knees, and scalp, without intense nocturnal pruritus.

- Impetigo – Superficial bacterial infection with honey-colored crusts, common in children, sometimes a secondary complication of scabies.

- Insect Bites (Bedbugs, Fleas, Lice) – Itchy papules in exposed areas, often grouped or linear, without burrows.

- Lichen Planus – Purplish, flat-topped papules with Wickham’s striae, mostly on the wrists and ankles.

- Tinea (Fungal Infections) – Annular (ring-shaped) scaly patches with central clearing, common in tinea corporis (body) and tinea pedis (feet).

- Drug Reactions (Fixed Drug Eruption, Hypersensitivity Rash) – Widespread rash following medication use, often with systemic symptoms like fever.

Treatment can be classified into 2: Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic

Non-pharmacologic

The non-pharmacological strategies are crucial complements to medication and help break the cycle of transmission in both household and community settings:

- Personal Hygiene – maintain good personal hygiene by bathing daily and keeping fingernails short and clean to minimize scratching and skin damage.

- Washing Clothes and Bedding – wash all clothing, bed linens, towels, and personal items used in the previous 3 days in hot water (at least 60°C) and dry in a hot dryer or under the sun to kill mites and eggs.

- Isolation of Items – items that cannot be washed should be sealed in plastic bags for at least 72 hours to 7 days, as mites cannot survive long without a human host.

- Environmental Cleaning – clean living areas, especially furniture, mattresses, and floors, by vacuuming and wiping surfaces to remove mites and prevent reinfestation.

- Treatment of Close Contacts – all household members and close physical contacts should be treated simultaneously, even if they are asymptomatic, to prevent re-infection.

- Health Education – Educate patients and caregivers on the nature of scabies, its transmission, and the importance of completing treatment and hygiene measures.

Pharmacologic

- Specific treatment: Benzyl benzoate (25%) is the first choice in Nigeria since it readily available and cheap.3 It should be diluted to 12.5% for children and quarter strength for infants under 6 months. It must be applied all over the body from head to toe in infants and from the neck down in older children for at least 12 hours. Retreatment is recommended after one week, or it can be applied daily for three days. Other medications that are available in Nigeria include topical permethrin 5% cream, oral ivermectin and sulfur ointment.

- Symptomatic treatment: as itching may persist even after mite eradication. Oral antihistamines (e.g., loratadine) help reduce itching, while topical corticosteroids (e.g., hydrocortisone) can ease inflammation. Moisturizers also help restore the skin barrier and reduce irritation.

- Treatment of complications: Complications such as secondary bacterial infections (e.g., impetigo or cellulitis) may occur, requiring topical or oral antibiotics. Severe cases can lead to glomerulonephritis or rheumatic fever, making early diagnosis and treatment crucial. Proper scabies management includes both mite eradication and symptom control to prevent recurrence and complications.

A 6-year-old child from an affluent background, whose father is a consultant physician, presented with complaints of intense pruritus, particularly at night, accompanied by a rash localized to the hands, wrists, and abdomen. The parents were initially resistant to the possibility of scabies, asserting that such a condition typically affects individuals in unhygienic or low-income settings. Prior to presentation, the child had been administered multiple antihistamines with no clinical improvement. Physical examination revealed characteristic burrows and papular lesions, notably in the inter-digital spaces and on the trunk. A confirmatory diagnosis of scabies was established through microscopic identification of Sarcoptes Scabiei from skin scrapings. Following counseling, parents came to understand that scabies are primarily transmitted through close personal contact and may affect individuals irrespective of their socioeconomic or hygienic status. The child, along with all household members, received appropriate scabicidal therapy, resulting in complete resolution of symptoms. This case emphasizes the importance of recognizing that scabies is not confined to disadvantaged populations and highlights the need for increased public awareness and early diagnosis to prevent transmission and complications.

Figure 2: Showing distribution of the scabietic rashes in the child

- Okpala C, Ezejiofor O, Anaje C, Enechukwu N, Echezona DF, Umenzekwe C. Clinical Profile of Scabies: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Southeastern Nigerian Hospital. Tropical Journal of Medical Research, 2023;22(1):173–179. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8361431.

- Biu AA, Machina IB, Ngoshe IY, Onyiche ET. Retrospective Study of Epidermal Parasitic Skin Diseases amongst Out- Patients of Skin Diseases Hospital, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 2018;22(2): 234-236.

- Ugbomoiko US, Oyedeji SA, Babamale OA, Heukelbach J. Scabies in Resource-Poor Communities in Nasarawa State, Nigeria: Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Factors Associated with Infestation. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(2):59. doi: 110.3390/tropicalmed3020059.

- Sule HM, Thacher TD. Comparison of ivermectin and benzyl benzoate lotion for scabies in Nigerian patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(2):392-5. PMID: 17297053.

- World Health Organization. Scabies. [2025 April 3]. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies.

- Chouela E, Abeldano A, Pellerano G, Hernandez MI. Diagnosis and treatment of scabies: a practical guide. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 2002;3(1):9-18.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world–its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(4):313-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03798.x.

- Girma A, Abdu I, Teshome K. Prevalence and determinants of scabies among schoolchildren in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2024;12:20503121241274757. doi: 10.1177/20503121241274757.

- Emanghe UE, Imalele EE, Ogban GI, Owai PA, Abraka BA. Awareness and knowledge of scabies and ringworm among parents of school-age children in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria: Implications for prevention of superficial skin infestations. Ann Afr Med. 2024;23(1):62-69. doi: 10.4103/aam.aam_82_23.

- Niode NJ, Adji A, Gazpers S, Kandou RT, Pandaleke H, Trisnowati DM, et al. Crusted Scabies, a Neglected Tropical Disease: Case Series and Literature Review. Infect Dis Rep. 202;14(3):479-491. doi: 10.3390/idr14030051.

More topics to explore

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Scabies

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

Scabies is a highly contagious skin condition caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. It is one of the major neglected tropical diseases which affect individuals of all ages, genders, ethnic backgrounds, and socioeconomic statuses. However, it is primarily associated with overcrowded living conditions and poverty rather than poor personal hygiene. Scabies has a global distribution, with an estimated 300 million cases reported annually. The disease is endemic in many developing countries, where limited access to healthcare and sanitation contributes to its persistence. In developed nations, scabies tends to occur in institutional outbreaks, particularly in hospitals, nursing homes, and long-term care facilities, where close contact among individuals facilitates its rapid spread.3 Despite its prevalence, scabies remain highly treatable with appropriate medical intervention and improved living conditions.

- Okpala C, Ezejiofor O, Anaje C, Enechukwu N, Echezona DF, Umenzekwe C. Clinical Profile of Scabies: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Southeastern Nigerian Hospital. Tropical Journal of Medical Research, 2023;22(1):173–179. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8361431.

- Biu AA, Machina IB, Ngoshe IY, Onyiche ET. Retrospective Study of Epidermal Parasitic Skin Diseases amongst Out- Patients of Skin Diseases Hospital, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 2018;22(2): 234-236.

- Ugbomoiko US, Oyedeji SA, Babamale OA, Heukelbach J. Scabies in Resource-Poor Communities in Nasarawa State, Nigeria: Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Factors Associated with Infestation. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(2):59. doi: 110.3390/tropicalmed3020059.

- Sule HM, Thacher TD. Comparison of ivermectin and benzyl benzoate lotion for scabies in Nigerian patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(2):392-5. PMID: 17297053.

- World Health Organization. Scabies. [2025 April 3]. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies.

- Chouela E, Abeldano A, Pellerano G, Hernandez MI. Diagnosis and treatment of scabies: a practical guide. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 2002;3(1):9-18.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world–its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(4):313-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03798.x.

- Girma A, Abdu I, Teshome K. Prevalence and determinants of scabies among schoolchildren in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2024;12:20503121241274757. doi: 10.1177/20503121241274757.

- Emanghe UE, Imalele EE, Ogban GI, Owai PA, Abraka BA. Awareness and knowledge of scabies and ringworm among parents of school-age children in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria: Implications for prevention of superficial skin infestations. Ann Afr Med. 2024;23(1):62-69. doi: 10.4103/aam.aam_82_23.

- Niode NJ, Adji A, Gazpers S, Kandou RT, Pandaleke H, Trisnowati DM, et al. Crusted Scabies, a Neglected Tropical Disease: Case Series and Literature Review. Infect Dis Rep. 202;14(3):479-491. doi: 10.3390/idr14030051.

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Scabies

Background

Scabies is a highly contagious skin condition caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. It is one of the major neglected tropical diseases which affect individuals of all ages, genders, ethnic backgrounds, and socioeconomic statuses. However, it is primarily associated with overcrowded living conditions and poverty rather than poor personal hygiene. Scabies has a global distribution, with an estimated 300 million cases reported annually. The disease is endemic in many developing countries, where limited access to healthcare and sanitation contributes to its persistence. In developed nations, scabies tends to occur in institutional outbreaks, particularly in hospitals, nursing homes, and long-term care facilities, where close contact among individuals facilitates its rapid spread.3 Despite its prevalence, scabies remain highly treatable with appropriate medical intervention and improved living conditions.

Further readings

- Okpala C, Ezejiofor O, Anaje C, Enechukwu N, Echezona DF, Umenzekwe C. Clinical Profile of Scabies: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Southeastern Nigerian Hospital. Tropical Journal of Medical Research, 2023;22(1):173–179. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8361431.

- Biu AA, Machina IB, Ngoshe IY, Onyiche ET. Retrospective Study of Epidermal Parasitic Skin Diseases amongst Out- Patients of Skin Diseases Hospital, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 2018;22(2): 234-236.

- Ugbomoiko US, Oyedeji SA, Babamale OA, Heukelbach J. Scabies in Resource-Poor Communities in Nasarawa State, Nigeria: Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Factors Associated with Infestation. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(2):59. doi: 110.3390/tropicalmed3020059.

- Sule HM, Thacher TD. Comparison of ivermectin and benzyl benzoate lotion for scabies in Nigerian patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(2):392-5. PMID: 17297053.

- World Health Organization. Scabies. [2025 April 3]. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies.

- Chouela E, Abeldano A, Pellerano G, Hernandez MI. Diagnosis and treatment of scabies: a practical guide. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 2002;3(1):9-18.

- Hay RJ, Steer AC, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world–its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(4):313-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03798.x.

- Girma A, Abdu I, Teshome K. Prevalence and determinants of scabies among schoolchildren in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2024;12:20503121241274757. doi: 10.1177/20503121241274757.

- Emanghe UE, Imalele EE, Ogban GI, Owai PA, Abraka BA. Awareness and knowledge of scabies and ringworm among parents of school-age children in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria: Implications for prevention of superficial skin infestations. Ann Afr Med. 2024;23(1):62-69. doi: 10.4103/aam.aam_82_23.

- Niode NJ, Adji A, Gazpers S, Kandou RT, Pandaleke H, Trisnowati DM, et al. Crusted Scabies, a Neglected Tropical Disease: Case Series and Literature Review. Infect Dis Rep. 202;14(3):479-491. doi: 10.3390/idr14030051.

Advertisement