Author's details

- Dr Aishatu Muhammad Jibril

- (MBBS, FMPaed)

- Department of Paediatrics, Federal University Dutse/Rasheed Shekoni Federal Teaching Hospital, Dutse, Jigawa state. Nigeria.

Reviewer's details

- Dr Taofik Ogunkunle

- MBBS, FWACP, FMCPaed, MPH

- Consultant Paediatrician, Dalhatu Araf Specialist Hospital, Lafia, Senior Clinical Research Scientist, International Foundation Against Infectious Disease in Nigeria (IFAIN)

- Date Uploaded: 2024-10-09

- Date Updated: 2025-02-05

Perinatology

Summary

The term perinatology was introduced in 1936 by the German paediatrician Pfaundler to define a period around the birth, that is characterise by a high fetal and neonate mortality, but with causes of death different from those observed in older infants.

The perinatal period as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) is the interval between 28 completed weeks of gestation (with babies weighing a minimum of 1000g) and the 1st completed week after birth. In industrialized countries the definition starts from 22 completed weeks of gestation with (minimum weight of 500 g). Unlike neonatal mortality that only accounts for deaths of live births, perinatal mortality in addition include stillbirths.

The perinatal period is a very delicate period in the lives of both mother and baby, being an indicator of the mother’s health (and the care she received) during pregnancy/ delivery and a determinant of the baby’s outcome later in life, it also plays an important role in providing the information needed to improve the health status of pregnant women and newborns. In the developing countries, perinatal health is still a major problem with almost half of under-five deaths now occur in the neonatal period which is the first 28 days after birth.

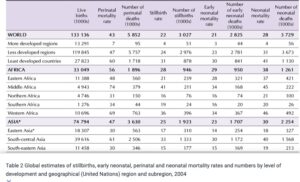

Table 1: Åhman, E.L., & Zupan, J. (2006). Neonatal and perinatal mortality: country, regional and global estimates. Adapted from Table 2 Global estimates of stillbirths, early neonatal, perinatal and neonatal mortality rates and numbers by level of development and geographical (United Nations) region and subregion, 2004

World-wide, about 7-9 million babies die annually, of which 98% occur in the tropics and developing

countries. Moreover, it is estimated that more than 3.3 million babies are stillborn every year; one in three of these deaths occurs during delivery and could largely be prevented.

Maternal and perinatal mortality are the most important adverse perinatal outcomes with a special impact on developing countries, where near almost 600.000 maternal deaths and near 7 million perinatal deaths occur every year.

The perinatal mortality rate ranges from 40 to 60 per 1,000 live births in most developing countries, but it is between 6 and 10 in industrial countries. There is always problem of knowing the exact magnitude of perinatal mortality rate due to poor or lack of recording. Most of the figures in developing countries, usually come from hospital statistics, these numbers have been calculated based on estimates, so therefore reality could be even worse.

The highest rates of deaths and morbidity occur among the poor, rural communities, where many challenges to improve Mother and Neonatal health remain. In addition, some religious and sociocultural norms adversely influence health-seeking behaviour and expose women to discriminatory practices which pose serious health risks.

In many societies, neonatal deaths and stillbirths are not perceived as a problem, largely because they are very common. Many communities have adapted to this situation by not recognizing the birth as complete, and by not naming the child, until the newborn infant has survived the initial period. Vital registration systems usually do not record and report stillbirths.

Maternal mortality in developing countries is given least attention, despite the, fact that almost all of the suffering and death is preventable with proper management.

In developing countries, just over 40% of deliveries occur in health facilities and little more than one in two takes place with the assistance of a doctor, midwife or qualified nurse.and mortality.

Most mothers receive insufficient family planning advice and ante natal care or none at all and deliver without access to skilled obstetrical care when complications develop.

The world has made substantial progress in child survival since 1990. Globally, the number of neonatal deaths declined from 5.0 million in 1990 to 2.3 million in 2022. However, the decline in neonatal mortality from 1990 to 2022 has been slower than that of post-neonatal under-5 mortality. Moreover, the gains have reduced significantly since 2010, and 64 countries will fall short of meeting the Sustainable Development Goals target for neonatal mortality by 2030 unless urgent action is taken.

Perinatal mortality occurs due to a complex interaction of individual level factors relating to maternal lifestyle and maternal obstetric complications, which could be exacerbated by underlying community-level factors, such as lack of access to good quality maternal and newborn health services

In the tropics neonatal deaths and stillbirths stem from poor maternal health, inadequate care during pregnancy, inappropriate management of complications during pregnancy and delivery, poor hygiene during delivery and the first critical hours after birth, and lack of newborn care.

Factors such as women’s status in society, their nutritional status at the time of conception, early childbearing, too many closely spaced pregnancies and harmful practices, such as inadequate cord care, letting the baby stay wet and cold, discarding colostrum and feeding other food, are deeply rooted in the cultural fabric of societies and interact in various ways.

In tropical countries, cultural and socioeconomic issues commonly have more impact on women in pregnancy.Many women do not have access to services or the capacity to control their fertility, which can lead to unplanned and inappropriately timed pregnancies which can sometimes be life-threatening.

Health workers at primary and secondary level of care often lack the skills to meet the needs of newborn infants, since the recognition of opportunity is only just emerging in countries, and their experience in this area is therefore limited.

Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa(SSA) have experienced conflicts in recent years. Studies have shown that conflicts is a barrier to facility-based deliveries which may result from destruction of health infrastructure and a lack of skilled health personnel, leading to an increase in the risk of perinatal mortality due to unassisted births and a lack of timely intervention or provision of life saving emergency perinatal services.

Maternal Humman Immunodeficiency Virus(HIV) status leads to an increased risk of stillbirth and death in the neonatal period. HIV-positive mothers are more likely to have low birth weight neonates than HIV-negative mothers, with low birth weight being an established risk factor for neonatal deaths.

Poverty remains an underlying factor associated with poor birth outcomes, it may result in delay or inability to seek care in the hospital. Poverty results in the inability to afford health care costs, which leads to poor utilization of health care services, thus increasing the risk of perinatal mortality.

Malaria infection during pregnancy is a major public health problem in SSA due to high burden and mortality and is known to be associated with higher rates of stillbirth, premature delivery, low-birth-weight neonates and neonatal death.

During drought periods, water becomes scarce and pregnant women are most likely to resort to unsafe water sources, making them more vulnerable to waterborne diseases, such as cholera and diarrhoea, which are known causes of perinatal mortality. Additionally, during periods of droughts, food production is greatly affected, which could lead to malnutrition an indirect cause of perinatal mortality.

Access to safe delivery and planning for expected and unexpected events is associated with reduced maternal and neonatal death.

In general, tackling perinatal mortality within the sub-regions of SSA would involve coordinated national and international efforts by governments and non-govern-mental organisations, as well as strengthening individual countries healthcare systems.

Other measures include:

- Effective prevention and management of conditions in late pregnancy,childbirth and the early newborn period are likely to reduce the numbers of maternal deaths

- Routine care during childbirth, including monitoring of labour and newborn care at birth and during the first week

- Management of pre-eclampsia, eclampsia and its complications;

- Management of difficult labour with safe, appropriate medical techniques;

- Management of postpartum haemorrhage;

- Newborn resuscitation when necessary, immediate breast-feeding, warmth, hygiene (especially for delivery and cord care)

- Management of preterm labour, birth and appropriate care for preterm and small babies

- The inclusion of a strong newborn component in emergency preparedness and response plans especially for countries experiencing political instability, conflicts, climate change and other potentially destabilizing conditions is highly needed.

- Management of maternal and newborn infections.

- Safe and clean delivery, early detection and management of sexually transmitted diseases, infections and complications during pregnancy and delivery, all interventions should be available, attainable and cost-effective.

- Universal access for women to care in pregnancy and childbirth and care of the newborn

- Education of the public on the need for early booking (registration for antenatal care) when pregnant, proper antenatal care during pregnancy and supervised delivery, regular upgrading of neonatal intensive care facilities and regular retraining of health personnel on intrapartum care.

- Address the health inequality caused by conflict within SSA countries by providing proper health,

- Removal of financial barriers to the utilization of healthcare services during pregnancy and facility-based deliveries would improve access to quality antenatal, delivery and postnatal care.

- infrastructure, equipment, medicines and skilled health personnel.

- Ensure pregnant women are given Tetanus toxoid immunization to reduce neonatal and maternal tetanus deaths.

- Intensify the current preventative measures for malaria, such as providing pregnant women with insecticide-treated bed nets (ITN) and intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) with antimalarial medications.

- Prophylactic iron and folate supplements are recommended where anaemia is common and identified, with screening.

- Skilled birth attendance for all women and emergency obstetric care for women with complications during and after pregnancy.

- Critical intervention packages that reduce maternal deaths, stillbirths, and early neonatal deaths, the “triple return.” which together with family planning and antenatal and postnatal care, ensure the continuum of care for all women and babies.

- In the long term, the combine education, improvement in the socioeconomic status of women and family planning information and services is what will have the highest impact on perinatal mortality reduction.

Maternal and newborn health (MNH) outcomes are intricately linked; maternal deaths significantly affect newborn survival and development. Therefore, appropriate technologies for most critical medical problems and complications are best delivered within a programme that ensures a continuum of care for the woman and her baby throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period.

And these care should be at the primary care level for all pregnant women and at higher levels of care for women and babies with complications.

- Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM), is a global initiative that address maternal deaths.

- Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP), a global initiative that address stillbirths and neonatal deaths, aim to accelerate and track progress in improving maternal, perinatal and newborn health and well-being.

- WHO also recommends that the ‘essential packages of interventions for low and middle-income settings’ should be provided across the continuum of care to improve Maternal and Neonatal Health, interventions should include family planning, appropriate antenatal care, immediate thermal care for newborns and early initiation of exclusive breastfeeding among others

- Maternal and Child care Care which focuses on the reduction of maternal, perinatal, infant and childhood mortality and morbidity and the promotion of reproductive health and the physical and psychosocial development of the child and adolescent within the family.

- Maternal and Child Health Week (MNCHW) was introduced-amongst other measures, as a priority and strategic action to accelerate the reduction of maternal and child deaths by delivering an integrated package of highly cost-effective Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health services/interventions.

- Some countries in the tropics like Nigeria introduced the Subsidy Reinvestment and Empowerment Programme Maternal and Child Health Project (SURE-P MCH), by increasing access to skilled birth attendance (SBA) and antenatal care (ANC) within the catchment areas of 500 facilities in the country.

- National Midwifery Service Scheme which was designed to increase coverage of skilled birth attendants in rural Primary Health Care(PHCs) to reduce maternal, newborn and child mortality

- The Integrated maternal, neonatal and child health Strategy aimed at fasttracking coverage of effective interventions along the continuum of care towards the reduction of maternal, neonatal and child morbidity and mortality in line with Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4 and 5 targets. This strategy document is in review, in order to reflect the SDG target for NMR of 12/1000 live birth by 2030.

- Essential Newborn Care Course, aim to ensure health workers have the skills and knowledge to provide appropriate care at the most vulnerable period in a baby’s life

- Community Based Newborn Care (CBNC) Course which is aimed at increasing the coverage of household and community interventions that will reduce newborn and child mortality and promote the healthy growth and development of young children. It also provide a legal framework for empowering community health workers (CHOs and CHEWs) to provide quality maternal and newborn care services, especially at PHCs. And addresses the human resource shortages that militate the provision of critical Maternal and Newborn services

To address perinatal mortality in SSA, strategies should focus on community-based mobilization of women to seek adequate antenatal care services and facility-based deliveries, as well as improved nutrition, up-to-date immunizations and healthy water, sanitation and hygiene practices. Political leadership and commitment are also essential for continued progress.These interventions will reduce perinatal mortality in SSA, thereby setting the region on the path to achieving the SDG target by 2030.

A 28-year-old woman in her third pregnancy, living in a rural area, experienced perinatal mortality due to complications arising from a lack of consistent prenatal care. She had unmanaged hypertension during pregnancy, which contributed to fetal distress and stillbirth after prolonged labor. Limited access to healthcare and financial barriers prevented timely interventions, highlighting the need for improved maternal healthcare services.

- 1. World Health Organization. Neonatal and perina- tal mortality: Country, regional and global estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006.

- 2. World Health Organization. 2018 Progress Report: Reaching every newborn national 2020 milestones. World Health Organization; 2018 Mar.

- 3. National Population Commission [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International; 2014.

- 4. Chinkhumba J, De Allegri M, Muula AS and Robberstad B. Maternal and perinatal mortality by place of delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta- analysis of population-based cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2014 Dec; 14(1): 1014. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1014

- 5. Bernis L, Kinney MV, Stones W, et al. Stillbirths: Ending preventable deaths by 2030. The Lancet. 2016; 387(10019): 703–716. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00954-X

- 6. UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group and United Nations. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality Report 2017. UNICEF; 2017 Oct.

- 7. Wang H, Bhutta ZA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mor- tality, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 388(10053): 1725–1774.

- 8. Stringer EM, Vwalika B, Killam WP, et al. Deter- minants of stillbirth in Zambia. Obstetrics & Gyne- cology. 2011 May 1; 117(5): 1151–9. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182167627

- 9. Akombi BJ and Renzaho AM. Perinatal Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Meta-Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Annals of Global Health. 2019; 85(1): 106, 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2348Published: 12 July 2019Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s).

- 10. UNICEF. State of the World’s Children 2016: A fair chance for every child. UNICEF; 2016. https:// www.unicef.org/publications/files/UNICEF_ SOWC_2016.pdf.

- 11. Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006 Sep 30; 368(9542): 1189-200.

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Perinatology

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

The term perinatology was introduced in 1936 by the German paediatrician Pfaundler to define a period around the birth, that is characterise by a high fetal and neonate mortality, but with causes of death different from those observed in older infants.

The perinatal period as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) is the interval between 28 completed weeks of gestation (with babies weighing a minimum of 1000g) and the 1st completed week after birth. In industrialized countries the definition starts from 22 completed weeks of gestation with (minimum weight of 500 g). Unlike neonatal mortality that only accounts for deaths of live births, perinatal mortality in addition include stillbirths.

The perinatal period is a very delicate period in the lives of both mother and baby, being an indicator of the mother’s health (and the care she received) during pregnancy/ delivery and a determinant of the baby’s outcome later in life, it also plays an important role in providing the information needed to improve the health status of pregnant women and newborns. In the developing countries, perinatal health is still a major problem with almost half of under-five deaths now occur in the neonatal period which is the first 28 days after birth.

- 1. World Health Organization. Neonatal and perina- tal mortality: Country, regional and global estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006.

- 2. World Health Organization. 2018 Progress Report: Reaching every newborn national 2020 milestones. World Health Organization; 2018 Mar.

- 3. National Population Commission [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International; 2014.

- 4. Chinkhumba J, De Allegri M, Muula AS and Robberstad B. Maternal and perinatal mortality by place of delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta- analysis of population-based cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2014 Dec; 14(1): 1014. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1014

- 5. Bernis L, Kinney MV, Stones W, et al. Stillbirths: Ending preventable deaths by 2030. The Lancet. 2016; 387(10019): 703–716. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00954-X

- 6. UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group and United Nations. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality Report 2017. UNICEF; 2017 Oct.

- 7. Wang H, Bhutta ZA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mor- tality, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 388(10053): 1725–1774.

- 8. Stringer EM, Vwalika B, Killam WP, et al. Deter- minants of stillbirth in Zambia. Obstetrics & Gyne- cology. 2011 May 1; 117(5): 1151–9. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182167627

- 9. Akombi BJ and Renzaho AM. Perinatal Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Meta-Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Annals of Global Health. 2019; 85(1): 106, 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2348Published: 12 July 2019Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s).

- 10. UNICEF. State of the World’s Children 2016: A fair chance for every child. UNICEF; 2016. https:// www.unicef.org/publications/files/UNICEF_ SOWC_2016.pdf.

- 11. Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006 Sep 30; 368(9542): 1189-200.

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Perinatology

Background

The term perinatology was introduced in 1936 by the German paediatrician Pfaundler to define a period around the birth, that is characterise by a high fetal and neonate mortality, but with causes of death different from those observed in older infants.

The perinatal period as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) is the interval between 28 completed weeks of gestation (with babies weighing a minimum of 1000g) and the 1st completed week after birth. In industrialized countries the definition starts from 22 completed weeks of gestation with (minimum weight of 500 g). Unlike neonatal mortality that only accounts for deaths of live births, perinatal mortality in addition include stillbirths.

The perinatal period is a very delicate period in the lives of both mother and baby, being an indicator of the mother’s health (and the care she received) during pregnancy/ delivery and a determinant of the baby’s outcome later in life, it also plays an important role in providing the information needed to improve the health status of pregnant women and newborns. In the developing countries, perinatal health is still a major problem with almost half of under-five deaths now occur in the neonatal period which is the first 28 days after birth.

Further readings

- 1. World Health Organization. Neonatal and perina- tal mortality: Country, regional and global estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006.

- 2. World Health Organization. 2018 Progress Report: Reaching every newborn national 2020 milestones. World Health Organization; 2018 Mar.

- 3. National Population Commission [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International; 2014.

- 4. Chinkhumba J, De Allegri M, Muula AS and Robberstad B. Maternal and perinatal mortality by place of delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta- analysis of population-based cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2014 Dec; 14(1): 1014. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1014

- 5. Bernis L, Kinney MV, Stones W, et al. Stillbirths: Ending preventable deaths by 2030. The Lancet. 2016; 387(10019): 703–716. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00954-X

- 6. UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group and United Nations. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality Report 2017. UNICEF; 2017 Oct.

- 7. Wang H, Bhutta ZA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mor- tality, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 388(10053): 1725–1774.

- 8. Stringer EM, Vwalika B, Killam WP, et al. Deter- minants of stillbirth in Zambia. Obstetrics & Gyne- cology. 2011 May 1; 117(5): 1151–9. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182167627

- 9. Akombi BJ and Renzaho AM. Perinatal Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Meta-Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Annals of Global Health. 2019; 85(1): 106, 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2348Published: 12 July 2019Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s).

- 10. UNICEF. State of the World’s Children 2016: A fair chance for every child. UNICEF; 2016. https:// www.unicef.org/publications/files/UNICEF_ SOWC_2016.pdf.

- 11. Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006 Sep 30; 368(9542): 1189-200.

Advertisement