Author's details

- Dr. Solaja Olufemi Augustine

- (MBChB, FWACS)

- HOD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, General Hospital Mushin. Lagos, Nigeria.

Reviewer's details

- Dr. Jolayemi Waliyat. A

- (MBBS, MPH-Epid, FWACS, FMCOG)

- Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. Evercare Hospital Lekki, Lagos, Nigeria.

- Date Uploaded: 2024-10-28

- Date Updated: 2025-02-05

Pelvic Floor Prolapse

Key Messages

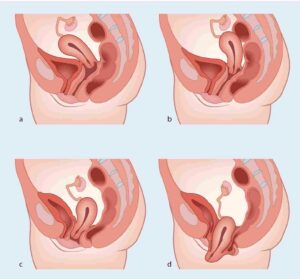

Pelvic organ prolapse or genital prolapse is the descent of the anterior vaginal wall, and/or the posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina (i.e., cases of vaginal vault after hysterectomy) from their normal position into the vaginal or through the introitus, or defined as the herniation of the female pelvic organs (vagina, uterus, bladder, and/or rectum) into or through the vagina. The herniation of these nearby organs into the vaginal space, gives rise to the different types of genital prolapse, and they are commonly referred to as cystocele (bladder) , rectocele ( rectum), or enterocele (intestine), etc. Studies have shown that mild descent of the pelvic organs is common and should not be considered pathologic.

Normal pelvic support is primarily provided by the levator ani muscles, when damaged, the levator ani muscles become more vertical in orientation and the vaginal opening widens, shifting support to the connective tissue attachments. It is due to defects of these support structures of the uterus and vagina that leads to the pathology.

The cause of prolapse is multifactorial but is primarily associated with any condition that leads to a prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure such as with recurrent pregnancy and vaginal delivery, which lead to direct pelvic floor muscle and connective tissue injury. Other associations are chronic cough, constipation, lifting of heavy weights or objects. These conditions are common and affect a progressively larger percentage of women as age advances. Whereas mortality from this condition is negligible, significant morbidity or deterioration in lifestyle/QoL may be associated with prolapse.

The true incidence of this disorder is not known because many of the cases are asymptomatic and many women feel shy to complain of uterovaginal prolapse. A woman’s lifetime risk of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is 12-19% with over 300 000 prolapse surgeries performed annually in the US alone. POP accounts for about 15-18% of hysterectomies, and uterovaginal prolapse is the most common indication for hysterectomy in postmenopausal women. Up to half of the normal female population will develop uterovaginal prolapse during their lifetime. In a retrospective study done in Oyo and Sokoto state, the prevalence of POP was put at 5.4% and 1.4% respectively with multiparity and advanced age been a common risk factor.

Uterovaginal prolapse could be congenital or acquired, though the congenital form is very rare. It most commonly occurs in grand multiparas and post-menopausal women. It is commoner in Caucasians than blacks. Other aetiological factors for pelvic organ prolapse include denervation associated with recurrent vaginal childbirth, (the parous women have a three-fold increased risk for pelvic organ prolapsed compared with nulliparous), collagen weakness, and oestrogen deficiency of menopause. Other causes include pregnancy, poor conduct of labour as occurs in bearing down before full cervical dilatation, the prolonged second stage of labour, deliveries of big baby(ies) and undue traction on the cervix during instrumental deliveries, Crede’s manoeuvre in delivery of the placenta. Even hysterectomy is a documented risk factor for prolapse. Other implicating factors in pelvic prolapse are anything that will cause increased intra-abdominal pressure, such as chronic cough, constipation with repeated straining at stool, intra-abdominal mass, or ascites. Lifting and carrying heavy loads may also contribute to the development of genital prolapse, thus the occupation of a women can also be a predisposing factor. Usually, women with POP presents with history of pelvic heaviness, dragging sensation and protrusion from the vagina. Prolapse can be complicated by acute urinary retention, stress incontinence, constipation, incarceration of the prolapse and decubitus ulceration.

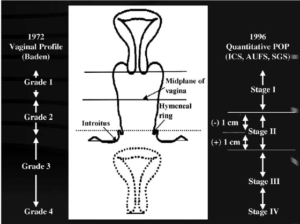

In 1996, the International Continence Society defined a system of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) to provide an internationally acceptable way of classifying prolapse that is reproducible. However, there was a classification that had been in use since 1972, and it is still majorly presently being used, the “Baden-Walker Halfway System for the Evaluation of Pelvic Organ Prolapse on Physical Examination”. The normal pelvic organs position is defined as grade 0, that means, no descent. When there is descent half the distance to the hymen is grade 1, then descent to the hymen is grade 2, and descent distal to the hymen is grade 3. Grade 4 is called procidentia, where the whole uterus is outside the vagina.

The diagram is courtesy of Researchgate

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225037789_Pelvic_Floor_Reconstruction.

Fig 1a- 1c

Pictures 1b and 1c courtesy of anatomy tools.org https://anatomytool.org/content/nine-landmarks-pelvic-organ-prolapse-quantification-popq-english-labels

The treatment of uterovaginal prolapse could be non-surgical/conservative and surgical, although treatment choice depends on the type and severity of symptoms, age, medical co-morbidities, desire for fertility and or coitus. The non-surgical techniques include lifestyle modifications such as weight reduction in obese patients, high fiber diet, avoidance of high impact exercise and lifting heavy objects, treatment of chronic cough. Others are pelvic floor muscle exercise, use of vaginal pessaries (which are of varying sizes and shapes), and Faradic electrical stimulation.The Vaginal pessary is useful during and immediately after pregnancy and also in those who are unfit or not ready for surgery. They are also useful in promoting the healing of decubitus ulcers. The surgical treatment is by hysterectomy and pelvic floor repair (anterior colporrhaphy and or posterior colpoperineorrhaphy), most often by vaginal hysterectomy. The advantage of vaginal hysterectomy over abdominal hysterectomy is shorter hospital stay and postoperative morbidity is less, there is no abdominal incision and less bleeding at surgery and it also allows for pelvic floor repair when needed. When the patient still desires fertility, the Manchester – Fothergill operation is performed (amputation of the cervix and approximation of the supporting ligaments). Other surgical options in managing patients with desire for fertility are sacrohysteropexy, ventrosuspension may be done. Colpocleisis (vaginal Closure), like the Lefort operation is undertaken in elderly patients who are no longer interested in sexual intercourse or very unstable patient. Procedures for correction of uterovaginal prolapse can also be done laparoscopically such as laparoscopy sacrohysteropexy.

In conclusion, pelvic organ prolapse has significant negative effects on a woman’s quality of life. Worldwide, vaginal hysterectomy with/without pelvic floor repair is the leading treatment method for patients with symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse.

A 58-year-old woman presents with pelvic pressure, vaginal bulging, and difficulty urinating, symptoms that have progressively worsened over the past year. She has a history of multiple vaginal deliveries and menopause at age 51. Physical examination reveals a grade 3 uterine prolapse. She is counselled on treatment options and expresses interest in trying conservative management, including pelvic floor exercises and the use of a pessary, before considering surgery.

- Iglesia C, Smithling KR. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(3):179–85.

- Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. BMJ-Brit Med J. 2016;354.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pelvic organ prolapse. ACOG. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25(6):397–408.

- Anozie Okechukwu B, Nwafor Johnbosco I, Esike Chidi U, Ewah Richard L, Edegbe Felix O, Obuna Johnson A, et al. Knowledge and Associated Factors of Pelvic Organ Prolapse among Women in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. J Women’s Health Dev. 2020;3(2):101–13.

- Fehintola AO, Awotunde OT, Ogunlaja OA, Olujide LO, Akinola SE, Oladeji SA, et al. Prospective Evaluation of Outcomes of Mechanical Devices in Women with Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Ogbomoso, South-Western Nigeria. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;11(4):461–73.

- Yakubu A, Panti AA, Ladan AA, Burodo AT, Hassan MA, Nasir S. Pelvic organ prolapse managed at Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto: A 10-year review. Sahel Med J. 2017;20(1):26.

- Abdur-Rahim ZF. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification Profile of Women in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Determinants and Symptom Correlation. Faculty Of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. NPMCN. 2017;

- Pollock GR, Twiss CO, Chartier S, Vedantham S, Funk J, Arif Tiwari H. Comparison of magnetic resonance defecography grading with POP-Q staging and Baden–Walker grading in the evaluation of female pelvic organ prolapse. Abdom. Radiol. 2021;46(4):1373–80.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, Rardin CR, Komesu Y, Harvie HS, et al. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(2):153-e1.

More topics to explore

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Pelvic Floor Prolapse

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

Pelvic organ prolapse or genital prolapse is the descent of the anterior vaginal wall, and/or the posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina (i.e., cases of vaginal vault after hysterectomy) from their normal position into the vaginal or through the introitus, or defined as the herniation of the female pelvic organs (vagina, uterus, bladder, and/or rectum) into or through the vagina. The herniation of these nearby organs into the vaginal space, gives rise to the different types of genital prolapse, and they are commonly referred to as cystocele (bladder) , rectocele ( rectum), or enterocele (intestine), etc. Studies have shown that mild descent of the pelvic organs is common and should not be considered pathologic.

- Iglesia C, Smithling KR. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(3):179–85.

- Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. BMJ-Brit Med J. 2016;354.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pelvic organ prolapse. ACOG. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25(6):397–408.

- Anozie Okechukwu B, Nwafor Johnbosco I, Esike Chidi U, Ewah Richard L, Edegbe Felix O, Obuna Johnson A, et al. Knowledge and Associated Factors of Pelvic Organ Prolapse among Women in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. J Women’s Health Dev. 2020;3(2):101–13.

- Fehintola AO, Awotunde OT, Ogunlaja OA, Olujide LO, Akinola SE, Oladeji SA, et al. Prospective Evaluation of Outcomes of Mechanical Devices in Women with Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Ogbomoso, South-Western Nigeria. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;11(4):461–73.

- Yakubu A, Panti AA, Ladan AA, Burodo AT, Hassan MA, Nasir S. Pelvic organ prolapse managed at Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto: A 10-year review. Sahel Med J. 2017;20(1):26.

- Abdur-Rahim ZF. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification Profile of Women in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Determinants and Symptom Correlation. Faculty Of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. NPMCN. 2017;

- Pollock GR, Twiss CO, Chartier S, Vedantham S, Funk J, Arif Tiwari H. Comparison of magnetic resonance defecography grading with POP-Q staging and Baden–Walker grading in the evaluation of female pelvic organ prolapse. Abdom. Radiol. 2021;46(4):1373–80.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, Rardin CR, Komesu Y, Harvie HS, et al. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(2):153-e1.

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Pelvic Floor Prolapse

Background

Pelvic organ prolapse or genital prolapse is the descent of the anterior vaginal wall, and/or the posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina (i.e., cases of vaginal vault after hysterectomy) from their normal position into the vaginal or through the introitus, or defined as the herniation of the female pelvic organs (vagina, uterus, bladder, and/or rectum) into or through the vagina. The herniation of these nearby organs into the vaginal space, gives rise to the different types of genital prolapse, and they are commonly referred to as cystocele (bladder) , rectocele ( rectum), or enterocele (intestine), etc. Studies have shown that mild descent of the pelvic organs is common and should not be considered pathologic.

Further readings

- Iglesia C, Smithling KR. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(3):179–85.

- Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. BMJ-Brit Med J. 2016;354.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pelvic organ prolapse. ACOG. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25(6):397–408.

- Anozie Okechukwu B, Nwafor Johnbosco I, Esike Chidi U, Ewah Richard L, Edegbe Felix O, Obuna Johnson A, et al. Knowledge and Associated Factors of Pelvic Organ Prolapse among Women in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. J Women’s Health Dev. 2020;3(2):101–13.

- Fehintola AO, Awotunde OT, Ogunlaja OA, Olujide LO, Akinola SE, Oladeji SA, et al. Prospective Evaluation of Outcomes of Mechanical Devices in Women with Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Ogbomoso, South-Western Nigeria. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;11(4):461–73.

- Yakubu A, Panti AA, Ladan AA, Burodo AT, Hassan MA, Nasir S. Pelvic organ prolapse managed at Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto: A 10-year review. Sahel Med J. 2017;20(1):26.

- Abdur-Rahim ZF. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification Profile of Women in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Determinants and Symptom Correlation. Faculty Of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. NPMCN. 2017;

- Pollock GR, Twiss CO, Chartier S, Vedantham S, Funk J, Arif Tiwari H. Comparison of magnetic resonance defecography grading with POP-Q staging and Baden–Walker grading in the evaluation of female pelvic organ prolapse. Abdom. Radiol. 2021;46(4):1373–80.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, Rardin CR, Komesu Y, Harvie HS, et al. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(2):153-e1.

Advertisement