Author's details

- Dr. AROJURAYE Soliudeen Adebayo

- BBS, FWACS, FMCOrtho, FACS.

- Department of Orthopaedics, National Orthopaedic Hospital, Dala, Kano, Nigeria

Reviewer's details

- Dr. Abdullah Adeyemi Badrudeen

- FWACS Senior Consultant Orthopaedic, Trauma and Spine surgeon

- Vedic Lifecare Hospital, Lekki, Lagos, Nigeria

- Date Uploaded: 2025-01-10

- Date Updated: 2025-12-20

Overview of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Key Messages

- The ACL is the main stabilizer of the knee, commonly injured in sports, especially through non-contact pivoting or direct blows.

- Diagnosis relies on clinical history, physical exams (Lachman, anterior drawer, pivot shift tests), and imaging (X-ray, MRI, arthroscopy).

- Treatment depends on age, activity, and injury severity; options include nonoperative rehab or surgical reconstruction.

- Rehabilitation is phased, focusing on reducing swelling, restoring motion, strengthening, and gradual return to activity.

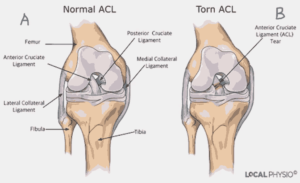

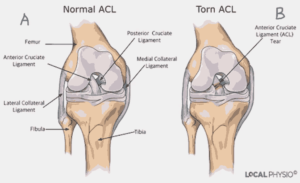

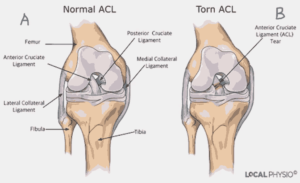

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is the main stabilizer of the knee joint for athletic pivotal activities. It is composed of two separate bundles, the anteromedial and the posterolateral. The intra-articular length of the ligament is between 28 and 31mm. The ACL has been described as a

multifascicular structure originating on the antero-medial aspect of the tibia, with a sagittal and coronal oblique course towards the posterior aspect of the medial side of the lateral femoral condyle. (Figure 1).

The ACL’s main blood supply is derived from branches of the middle genicular artery. These form a network in the synovial membrane surrounding the ligament, with secondary contributions from the medial and lateral geniculate at the tibial insertion. The bony attachments are of less nutritional importance.

With the increase in sports participation worldwide, injury to the ACL has become one of the most common athletic injuries and it is the most reconstructed ligament in the human body. In the 1970s, the torn ACL was considered the beginning of a progressive deterioration of the knee that often ended an athlete’s career. However, with the improvement in arthroscopy and sports medicine, many athletes now routinely return to play as soon as four to six months after an injury.

Source of Image: Atlanta’s Resource for Orthopaedic Surgery. https://www.atlantaboneandjoint.com/acltear.html

Figure 1: Diagrammatic representation of Major Knee Ligaments. A – Normal ACL, B – Torn ACL

Understanding the causative mechanism of ACL injury might help determine prevention methods. The most common injury mechanism involves no contact with others.

1. Noncontact pivot: The athlete is simply running and abruptly changes direction. The ACL is stressed by the rotation of the tibia, resulting in a tear. Women are at higher risk for ACL tears from noncontact injuries (4:1), but the contributing factors are ill-defined. Females have been shown to have increased tibial rotation and decreased hamstring activity, which might contribute to this gender difference. The quadriceps contraction may be of importance in injuring the ACL (Quadriceps dominance). Barrett and coworkers have calculated that an eccentric quadriceps contraction can generate up to 6000N. This far exceeds the strength of the ACL at 1700N. This force can be observed in basketball in the jump stop landing (Landing biomechanics). Females usually sustain ACL injuries at a younger age than males. The supporting leg is commonly injured in females whereas it is the kicking leg that is usually injured in males.

2. Contact Mechanism: A common mechanism in football or hockey is the blow to the outside of the knee when the knee is flexed and rotated. This initially injures the medial collateral ligament (MCL), and then, with further valgus, the ACL is torn.

The diagnosis of ACL tears is made clinically, through thorough medical history and clinical examination. This can be confirmed using imaging studies. Imaging studies can confirm this.

In a typical scenario, the patient describes a twisting injury to his knee, associated with a “popping” sensation in the knee. This is followed by immediate pain and swelling of the knee. Pain can range from minimal and transient to severe and long-lasting. It may be described as deep in the knee but is more often felt anterior on either side of the patellar tendon or laterally on the joint line. In about 80% of ACL injuries, individuals experience a popping, snapping, or tearing sensation. A rapid onset (usually within 3 hours) of swelling (hemarthrosis) is also seen in about eighty percent. Swelling is described as “a poor-man” MRI scan of the knee; in traumatic knee, a swelling is an indication of an underlying pathology. Weight-bearing leads to a feeling of the knee giving way or “just not feeling right.” The patient may indicate the feeling of the knee giving way with the “2-fist sign”. (Figure 2)

Picture source: National Orthopaedic Hospital, Dala, Kano, Nigeria

Figure 2: An athlete demonstrating the “2-fist sign” of his knee instability

When properly done, a physical examination can demonstrate all cases of complete ACL tears. The Lachman test is the most definitive and easily performed test for ACL tears. It is performed with the patient in the supine position. The knee is flexed to 30°, the femur is stabilized by the upper hand, and the tibia is pulled forward using the lower hand (Figure 3). The test is positive when the endpoint is soft. The main feeling is the lack of an endpoint to the anterior translation of the tibia. Comparing to the opposite side is important. Other clinical signs to demonstrate ACL tear include the anterior drawer test and pivot shift test. The pivot shift test is done with the patient lying on their back with the affected knee fully extended and the tibia internally rotated, the tester stresses the knee with a coupled valgus and internal rotation force and flexes the knee. An appreciable clunk felt around 30° of knee flexion indicates that the subluxated joint has reduced and indicates a complete ACL tear. Complete knee examinations are also done to rule out other associated injuries.

Picture source: National Orthopaedic Hospital, Dala, Kano, Nigeria

Figure 3: Demonstration of clinical signs in ACL injury diagnosis. (A) Anterior drawer test, (B) Lachman test.

Radiological examination of the knee should always start with plain radiographs. This will reveal ACL bony avulsions, significant osteochondral fractures, tibial plateau fractures, or segond fracture that is associated with ACL tears in about 75% of cases.

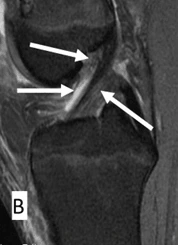

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is very useful in diagnosing ACL injury. Though, the diagnosis of ACL rupture is clinical and a good physical examination by an experienced physician is more reliable than an MRI. However, in a few situations, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will change your management of an injury. It may be required to differentiate between a cyclops lesion of the ACL and a bucket handle tear of the meniscus. The sensitivity and specificity of an MRI in diagnosing ACL tears are 86% and 95% respectively. Other important tests for diagnosing an ACL tear in the operating room are examination under anaesthesia EUA and diagnostic arthroscopy (Figure 5).

Picture source: National Orthopaedic Hospital, Dala, Kano, Nigeria

Figure 4: Sagittal view of Knee MRI showing ACL. (A) Normal ACL, (B) Torn AC

L

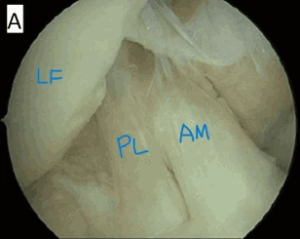

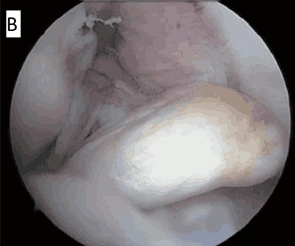

Picture source: National Orthopaedic Hospital, Dala, Kano, Nigeria

Figure 5: Arthroscopic anatomy of ACL. (A) Normal ACL, LF – Lateral femoral condyle, PL – Posterolateral bundle, AM – Anteromedial bundle. (B) Ruptured ACL

The treatment options for ACL injuries depend on many factors, including the patient's age, level of activity, chronicity of the injury, and associated injury to the meniscus and articular surface.

The older patient may be more likely to modify his/her lifestyle and accept nonoperative treatment, while the younger patient, who is involved in competitive sports, wants to return as quickly as possible to high-level sports without using a brace. Therefore, surgery is mandatory.

In acute cases, “PRICE” treatment of pain killer, rest, ice, compression, and elevation should be instituted till inflammation is resolved. Physical therapy should then follow to regain the full range of knee motion.

There are no hard and fast rules, such as waiting for a certain number of weeks before operative treatment when indicated. Some patients will have a good range of motion and no swelling in one week while other patients will take six or eight weeks to be ready for surgery. The time to operate is when the tissue is soft and compliant, and the range of motion is good.

Patients who may benefit from nonsurgical treatment include those with sedentary occupations or those who participate in less demanding sports (straight-line sporting) such as jogging and cycling. They have a better chance of successfully returning to their sports with nonoperative treatment. The non-operative treatment protocol is like the postoperative rehabilitation protocols of ACL reconstruction. The protocol is summarized in phases as follows:

Phase I: Immediate post-injury or post-surgery (0 to 2 weeks)

The goal of this phase is to reduce swelling, minimize pain, restore full extension, gradually improve flexion and to regain full active knee extension. The patient ambulates partial weight bearing using crutches. Quadriceps exercises are advised to be able to perform straight leg raise without lag. When climbing stairs, the non-injured side is leading, while the crutches and the injured limb are leading when going down the stairs.

Phase II: Intermediate (3 – 5 weeks)

The goal of rehabilitation in this phase is to maintain range of motion (ROM) and flexibility, to restore muscle strength, increase proprioception and neuromuscular responses, restore normal gait with stair climbing and eliminate instability. This continues with phase I intervention. ROM is continued including the use of a stationary bicycle, partial squat exercise and one-leg standing.

Phase III: Late / Chronic (6 to 8 weeks)

The goal is to achieve progressive strengthening, maintain ROM and flexibility, restore neuromuscular responses with plyometrics and advanced proprioceptive exercises and return to running. These are achieved by continuing to increase the intensity of proprioceptive training from phase II exercises to add for progressive agility training: lateral shuffle and cone drills (figure 8, forward/backwards running, T-Test)

Phase IV: Unrestricted return to work and sports (8 to 12+ weeks)

Additional intervention needed in this phase is to continue to progress with strengthening exercises with increasing resistance assuming proper form and technique. This also involves advanced phase III plyometric training to single leg, advanced agility training to sport-specific movements at competition speed and progress aerobic and metabolic conditioning appropriate for the sport.

Once it has torn, attempts to surgically repair ACL tears are not successful. Consequently, better results are obtained if the ACL is surgically reconstructed with another tendon. The surgical procedure is mostly performed using arthroscopic techniques. Using one or two small incisions on the knee, the graft is taken from the patellar tendon, hamstring tendons or peroneus longus tendon, and a tunnel is drilled into both the tibia and femur. The graft is threaded across the knee, The graft is then secured in position, most commonly by “wedging” a screw (interference screw) between the side of the bone and the tunnel. Alternatively, the graft can be secured by other techniques — staples, sutures, buttons, etc. These fixation devices are usually left in place permanently.

Figure 6: Knee Arthroscopy being performed

Figure 7: Peroneus Longus Graft being harvested using a tendon stripper.

Figure 8: Peroneus Longus graft prepared for ACL Reconstruction.

Figure 9: ACL graft is fixed to the tibia tunnel with an absorbable interference screw.

Pictures Sources: National Orthopaedic Hospital Dala Kano

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries are becoming increasingly common in sub-Saharan Africa due to rising participation in sports and physical activities. Limited access to advanced diagnostic tools, rehabilitation services, and surgical expertise poses significant challenges in managing ACL injuries effectively. Early detection and treatment, including physical therapy and, where possible, surgical reconstruction, are crucial for restoring function and preventing long-term joint damage. Increasing awareness, enhancing access to orthopedic care, and building capacity for sports injury management are key to improving outcomes in these settings.

A 27-year-old female sustained an ACL injury while playing soccer, feeling a “pop” in her right knee followed by immediate pain, swelling, and difficulty bearing weight. Physical examination revealed knee swelling, decreased range of motion, and a positive Lachman test, suggesting ACL instability. An MRI was recommended to confirm the diagnosis. After discussing treatment options, the patient opted for surgical repair followed by rehabilitation to support her return to sports.

1. Arojuraye SA, Salihu MN, Salahudeen A. Arthroscopic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Learning Curve: Analysis of Operating Time and Clinical Outcomes. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2024 Apr-Jun;14(2):208-211.

2. Alabi IA, Nkanta C, Okoh N, Arojuraye SA and Abbas AD. Functional Outcome of Arthroscopic Reconstruction of Chronic Anterior Cruciate ligament Rupture using Single-bundle Triple-weaved Hamstring Tendons in Northern Nigeria. International Journal of Orthopaedics Sciences 2020; 6(4): 533-538.

3. Leon S, Carol V. David S. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Anatomy, Physiology, Biomechanics, and Management. Clin J Sport Med 2012; 22(4): 349 – 355.

4. Douglas WA, Peter RK. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. In: Douglas WJ. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery; Reconstructive knee Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2008; 3rd Ed, 3: 132 – 153

5. Shelbourne KD, Benner RW, Ringenberg JD, Gray T. Optimal management of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: current perspectives. Orthop Res Rev. 2017;9:13-22

6. Bolgla LA. Gender issues in ACL injury. In: Giangarra CE, Manske RC, eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 49.

7. Brotzman SB. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Giangarra CE, Manske RC, eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 47.

8. Cheung EC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Miller MD, Thompson SR, eds. DeLee, Drez, & Miller’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 98.

9. Gokeler A, Dingenen B, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation and return to sport testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: where are we in 2022? Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2022;4(1):e77-e82.

10. Kalawadia JV, Guenther D, Irarrázaval S, Fu FH. Anatomy and biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament. In: Prodomos CC. The Anterior Cruciate Ligament: Reconstruction and Basic Science. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 201

8:chap 1.

More topics to explore

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Overview of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is the main stabilizer of the knee joint for athletic pivotal activities. It is composed of two separate bundles, the anteromedial and the posterolateral. The intra-articular length of the ligament is between 28 and 31mm. The ACL has been described as a

multifascicular structure originating on the antero-medial aspect of the tibia, with a sagittal and coronal oblique course towards the posterior aspect of the medial side of the lateral femoral condyle. (Figure 1).

The ACL’s main blood supply is derived from branches of the middle genicular artery. These form a network in the synovial membrane surrounding the ligament, with secondary contributions from the medial and lateral geniculate at the tibial insertion. The bony attachments are of less nutritional importance.

With the increase in sports participation worldwide, injury to the ACL has become one of the most common athletic injuries and it is the most reconstructed ligament in the human body. In the 1970s, the torn ACL was considered the beginning of a progressive deterioration of the knee that often ended an athlete’s career. However, with the improvement in arthroscopy and sports medicine, many athletes now routinely return to play as soon as four to six months after an injury.

Source of Image: Atlanta’s Resource for Orthopaedic Surgery. https://www.atlantaboneandjoint.com/acltear.html

Figure 1: Diagrammatic representation of Major Knee Ligaments. A – Normal ACL, B – Torn ACL

1. Arojuraye SA, Salihu MN, Salahudeen A. Arthroscopic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Learning Curve: Analysis of Operating Time and Clinical Outcomes. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2024 Apr-Jun;14(2):208-211.

2. Alabi IA, Nkanta C, Okoh N, Arojuraye SA and Abbas AD. Functional Outcome of Arthroscopic Reconstruction of Chronic Anterior Cruciate ligament Rupture using Single-bundle Triple-weaved Hamstring Tendons in Northern Nigeria. International Journal of Orthopaedics Sciences 2020; 6(4): 533-538.

3. Leon S, Carol V. David S. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Anatomy, Physiology, Biomechanics, and Management. Clin J Sport Med 2012; 22(4): 349 – 355.

4. Douglas WA, Peter RK. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. In: Douglas WJ. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery; Reconstructive knee Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2008; 3rd Ed, 3: 132 – 153

5. Shelbourne KD, Benner RW, Ringenberg JD, Gray T. Optimal management of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: current perspectives. Orthop Res Rev. 2017;9:13-22

6. Bolgla LA. Gender issues in ACL injury. In: Giangarra CE, Manske RC, eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 49.

7. Brotzman SB. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Giangarra CE, Manske RC, eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 47.

8. Cheung EC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Miller MD, Thompson SR, eds. DeLee, Drez, & Miller’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 98.

9. Gokeler A, Dingenen B, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation and return to sport testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: where are we in 2022? Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2022;4(1):e77-e82.

10. Kalawadia JV, Guenther D, Irarrázaval S, Fu FH. Anatomy and biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament. In: Prodomos CC. The Anterior Cruciate Ligament: Reconstruction and Basic Science. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 201

8:chap 1.

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Overview of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Background

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is the main stabilizer of the knee joint for athletic pivotal activities. It is composed of two separate bundles, the anteromedial and the posterolateral. The intra-articular length of the ligament is between 28 and 31mm. The ACL has been described as a

multifascicular structure originating on the antero-medial aspect of the tibia, with a sagittal and coronal oblique course towards the posterior aspect of the medial side of the lateral femoral condyle. (Figure 1).

The ACL’s main blood supply is derived from branches of the middle genicular artery. These form a network in the synovial membrane surrounding the ligament, with secondary contributions from the medial and lateral geniculate at the tibial insertion. The bony attachments are of less nutritional importance.

With the increase in sports participation worldwide, injury to the ACL has become one of the most common athletic injuries and it is the most reconstructed ligament in the human body. In the 1970s, the torn ACL was considered the beginning of a progressive deterioration of the knee that often ended an athlete’s career. However, with the improvement in arthroscopy and sports medicine, many athletes now routinely return to play as soon as four to six months after an injury.

Source of Image: Atlanta’s Resource for Orthopaedic Surgery. https://www.atlantaboneandjoint.com/acltear.html

Figure 1: Diagrammatic representation of Major Knee Ligaments. A – Normal ACL, B – Torn ACL

Further readings

1. Arojuraye SA, Salihu MN, Salahudeen A. Arthroscopic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Learning Curve: Analysis of Operating Time and Clinical Outcomes. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2024 Apr-Jun;14(2):208-211.

2. Alabi IA, Nkanta C, Okoh N, Arojuraye SA and Abbas AD. Functional Outcome of Arthroscopic Reconstruction of Chronic Anterior Cruciate ligament Rupture using Single-bundle Triple-weaved Hamstring Tendons in Northern Nigeria. International Journal of Orthopaedics Sciences 2020; 6(4): 533-538.

3. Leon S, Carol V. David S. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Anatomy, Physiology, Biomechanics, and Management. Clin J Sport Med 2012; 22(4): 349 – 355.

4. Douglas WA, Peter RK. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. In: Douglas WJ. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery; Reconstructive knee Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2008; 3rd Ed, 3: 132 – 153

5. Shelbourne KD, Benner RW, Ringenberg JD, Gray T. Optimal management of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: current perspectives. Orthop Res Rev. 2017;9:13-22

6. Bolgla LA. Gender issues in ACL injury. In: Giangarra CE, Manske RC, eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 49.

7. Brotzman SB. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Giangarra CE, Manske RC, eds. Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 47.

8. Cheung EC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Miller MD, Thompson SR, eds. DeLee, Drez, & Miller’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 98.

9. Gokeler A, Dingenen B, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation and return to sport testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: where are we in 2022? Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2022;4(1):e77-e82.

10. Kalawadia JV, Guenther D, Irarrázaval S, Fu FH. Anatomy and biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament. In: Prodomos CC. The Anterior Cruciate Ligament: Reconstruction and Basic Science. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 201

8:chap 1.

Advertisement