Author's details

- Dr Hauwa Umar Mustapha

- MBBS, MWACP in paediatrics, Senior Registrar

- Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano.

Reviewer's details

- Dr Afolayan Folake Moriliat

- (MBBS, MSc Tropical Pediatrics, FMCPaed)

- Consultant paediatrician at Kwara State Teaching Hospital, Ilorin.

- Date Uploaded: 2024-12-11

- Date Updated: 2025-02-06

Oncologic Metabolic Emergencies

Summary

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death among children and adolescents worldwide. Each year, an estimated 400,000 children and adolescents are diagnosed with cancer, and approximately 90,000 deaths occur annually (1).

Alarmingly, around 80% of cancer-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Nigeria, where limited access to early diagnosis, specialized treatment, and supportive care contributes to poorer outcomes. Strengthening healthcare systems in these regions is essential to improve survival rates and reduce the global burden of childhood malignancies.”

Childhood cancers represent a significant global health challenge, with varying incidence and distribution patterns across different regions. The burden is particularly notable in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where access to early diagnosis and treatment is limited, contributing to poorer outcomes compared to high-income countries.

In India, boys majorly had leukaemia and lymphoma while girls had mostly had leukaemia and brain tumours (2). A study done by two tertiary institutions that are the only cancer centers in Ghana found that lymphomas and leukaemia were the most common cancer in children (3. A tertiary institution in Nigeria found lymphomas especially the Burkitt subtype to be predominant in children (4).

Childhood cancers such as neuroblastomas, soft tissue sarcomas (e.g., rhabdomyosarcoma), and bone tumors (e.g., osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma) are also significant contributors to the pediatric cancer burden. In sub-Saharan Africa, unique factors like infectious agents (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV) and environmental exposures (e.g., pesticides, aflatoxins) contribute to the distinct cancer patterns observed.

Despite advances in treatment, survival disparities persist due to late presentation, limited access to diagnostic tools, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure in many LMICs. Strengthening early detection, improving cancer registries, and expanding access to care are critical steps in reducing the global burden of childhood malignancies.

A study in the U.S. by Sarah Klemencic et al., published in the Western Journal of Medicine, identified febrile neutropenia, tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), and hypercalcemia as the most common oncologic emergencies in pediatric patients.

In Nigeria, a study conducted at Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) Zaria by S.A. Adewuyi et al. in April 2018 highlighted thrombocytopenia and anemia as the predominant oncologic emergencies. Similarly, at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH), anemia and thrombocytopenia were reported as the most frequent emergencies, followed by febrile neutropenia.

Despite advancements in cancer management, many children continue to present with conditions that necessitate urgent, life-saving interventions. Oncologic emergencies significantly contribute to increased morbidity and mortality in pediatric cancer patients. Early recognition and timely intervention are essential, and maintaining a high index of suspicion in all children diagnosed with cancer is critical for improving outcomes.

Initial presentation of primary disease.

Complication/ progression of known disease.

Complication of therapy.

- Metabolic emergencies

- Haematologic emergencies

- Mechanical/compressional emergencies

- Infections and inflammation emergencies.

- Others.

These are to life-threatening conditions that arise from metabolic disturbances caused by cancer or its treatment in children. These include complications like tumor lysis syndrome (rapid breakdown of tumor cells leading to electrolyte imbalances), hypercalcemia of malignancy, syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH) and hyponatremia. These emergencies require prompt recognition and management to prevent severe organ dysfunction or death.

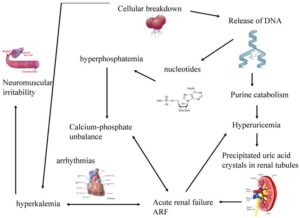

Tumour Lysis Syndrome (TLS) describes the clinical and laboratory sequelae that result from the rapid release of intracellular contents of dying cancer cells. It is characterized by the release of potassium, phosphorous, and nucleic acids from cancer cells into the blood stream. It has the potential to cause hyperkalaemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperuricaemia and secondary hypocalcaemia (figure 1).

Figure 1: Pathophysiology of TLS Image source: benhviennhi.org.vn

- Large tumour burden

- Bulky disease >10 cm in diameter

- White blood cell >50,000 /μL

- High growth fraction e.g. Burkitt’s lymphoma

- High pretreatment serum LDH or uric acid

- Preexisting renal insufficiency

- Volume depletion

- Laboratory TLS (3 to +7 days Rx) with 2 or more of the following:

- Uric acid ≥8 mg/dL (476 μM/L) or 25% increase.

- K+ ≥6.0 mmol/L or 25% increase.

- PO4 ≥6.5 mg/dL (2.1 mmol/L) or 25% increase.

- Ca++ ≤7 mg/dL (1.75 mmol/L) or 25 % decrease.

- The clinical diagnosis of TLS are based on laboratory evidence of TLS plus one or more of the following:

- Increased serum creatinine (1.5x ULN)

- Cardiac Arrhythmia

- Seizure

- Hyperhydration

- Alkalinization : increases solubility uric acid 10-fold. PH of 8

- Allopurinol (blocks catabolism of hypoxanthine to uric acid; may get precipitation of hypoxanthine)

- Rasburicase (urate oxidase degrades uric acid to more soluble allantoin)

- Treat hyperkalaemia (≥ 6mmol/l)

- Discontinue all exogenous source of potasssium

- Stabilise the cardiac membrane with ca-gluconate @1-2mmol/kg IV in two divided doses slowly.

- Sodium bicarbonate 1-2mg/kg IV

- Beta 2 agonist like salbutamol

- Glucose insulin infusion 0.5g/kg/h + 0.1 unit/kg/h

- Ion binding resins e.g. Kayexalate/ Resonium A [1g/kg po q6h]

- Dialysis

- Hyperhydration

- Oral phosphate binder

- Dialysis

- Hyperhydration

- Allopurinol (10mg/kg/day)

- Rasburicase (0.2mg/kg IV)

- Dialysis

This is defined as serum calcium levels >3mmol/l (12mg/dl) or ionized calcium <1.29mmol/l. The causes include bone metastasis, leukemia, osteosarcoma and rhadomyosarcoma. Pathophysiologically, systemic release of parathyroid release hormone or vitamin D analogue by tumour cells or effect of prostaglandins and interleukin leading to bone resorption

The clinical manifestations include constipations, bone pains, fatigue, confusion, lethargy, seizures, polydipsia, coma and cardiac arrest.

- Serum calcium and phosphate.

- ECG shows a prolonged PR interval, wide T wave, shortened QT interval

- X-ray can show discrete skeletal lesions but not demonstrable in 30 % of patients.

- Intravenous hydration with normal saline (3L/m2/day)

- Diuresis with IV frusemide (1mg/kg/dose)

- IV bisphosphonate inhibits bone resorption e.g. Etidronate/Pamidronate [1mg/kg, IV)

- Radiotherapy and or chemotherapy

- Dialysis (rarely needed)

Excessive secretion of ADH accompanying low serum sodium concentration. Etiology is multifactorial, usually occurs for reasons unrelated to therapy like primary CNS disease, stress, paraneoplastic, pulmonary disease, surgery or from side effects of vincristine or cyclophosphamide treatment. The common clinical manifestations are: malaise, headache, confusion, lethargy, seizures, coma.

- Decrease serum Na level with Hypo-osmolar plasma.

- Urinary Na must be ≥ 20mmol/l with high osmolality.

- There must be intact pituitary, adrenal, renal & hepatic functions.

- There shouldn’t be any use of drugs, including diuretics.

- There must be no evidence of dehydration.

- There must be significant improvement following fluid restriction.

- Salt and water restriction

- Administration of hypertonic saline-3%NaCl

- Treat underlying cause

- Drug Therapy (e.g. Demeclocycline)

This when the blood glucose of <2.2mmol/l. The clinical features include neuroglycopenic or autonomic symptoms. It could be caused by insulinoma which can present with a large retroperitoneal lesion. Other tumours like hepatocellular carcinoma or extensive hepatic metastasis

- Production of insulin-like substance by some tumors

- Depletion of glycogen stores from the liver.

- Intravenous glucose infusion.

- Glucagon injection.

- Octreotide.

Childhood oncologic emergencies in sub-Saharan Africa are a critical concern due to delayed diagnosis, limited access to specialized care, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure. Common emergencies include tumor lysis syndrome, septic shock, and airway obstruction from tumors, which require prompt intervention. Early detection, improved healthcare resources, and increased awareness of pediatric cancers are vital for timely treatment and better outcomes. Strengthening healthcare systems and training healthcare providers are key to addressing these life-threatening emergencies in the region.

A 7-year-old boy, diagnosed with Burkitt’s lymphoma, developed tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) two days after starting chemotherapy. TLS occurred when his cancer cells broke down too quickly, releasing substances that overwhelmed his body. He experienced severe weakness, vomiting, muscle pain, reduced urination, and rapid breathing. Tests showed high potassium, uric acid, and phosphate levels, leading to kidney and heart problems. The patient was treated with IV fluids, medications, and monitoring, which stabilized his condition. This case highlights the importance of early recognition and treatment of TLS in pediatric cancer patients.

- World Health Organization. Childhood Cancer. Dec 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer-in-children Accessed Dec 2024.

- Satyanarayana L, Asthana S, Labani S P. Childhood cancer incidence in India: a review of population-based cancer registries. Indian Pediatr. 2014 Mar;51(3):218-20. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0377-0. PMID: 24736911.

- Winifred E. Owusu, Johanita R. Burger, Martha S. Lubbe, Rianda Joubert, Marike Cockeran, Incidence patterns of childhood cancer in two tertiary hospitals in Ghana from 2015 to 2019: A retrospective observational study, Cancer Epidemiology, Volume 87, 2023, 102470, ISSN 1877-7821, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2023.102470. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877782123001509)

- Mohammed A, Aliyu HO. Childhood cancers in a referral hospital in northern Nigeria. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2009 Jul;30(3):95-8. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.64253. PMID: 20838544; PMCID: PMC2930295.

- Klemencic, Sarah & Perkins, Jack. (2019). Diagnosis and Management of Oncologic Emergencies. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 20. 316-322. 10.5811/westjem.2018.12.37335.

- Nelson’s textbook of pediatrics 21st edition by Kleigman, Behrman, Jenson and Stanton

- Principles and practice of pediatric oncology 4th edition by Philip.A. Pizzo and David.G. Poplack

- Williams Haematology,6th edition,by Ernest Beutler M.D,etal.

- Zinner SH. Changing epidemiology of infections in patients with neutropenia and cancer: emphasis on gram-positive and resistant bacteria. Clin Infect Dis.1999;29(3):490–4.

- Melendez E, Harper MB. Risk of serious bacterial infection in isolated and unsuspected neutropenia. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):163–7.

- Moon JM, Chun BJ. Predicting the complicated neutropenic fever in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(11):802–6.

- Roland T. Skeel- Handbook of cancer chemotherapy

- Rheingold & Lange, “Oncologic Emergencies”, in Principles & Practice of Pediatric Oncology, eds Pizzo, Poplack.

- Nazemi Emerg Med Clin N Am 27 (2009) 477–495

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Oncologic Metabolic Emergencies

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death among children and adolescents worldwide. Each year, an estimated 400,000 children and adolescents are diagnosed with cancer, and approximately 90,000 deaths occur annually (1).

Alarmingly, around 80% of cancer-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Nigeria, where limited access to early diagnosis, specialized treatment, and supportive care contributes to poorer outcomes. Strengthening healthcare systems in these regions is essential to improve survival rates and reduce the global burden of childhood malignancies.”

- World Health Organization. Childhood Cancer. Dec 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer-in-children Accessed Dec 2024.

- Satyanarayana L, Asthana S, Labani S P. Childhood cancer incidence in India: a review of population-based cancer registries. Indian Pediatr. 2014 Mar;51(3):218-20. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0377-0. PMID: 24736911.

- Winifred E. Owusu, Johanita R. Burger, Martha S. Lubbe, Rianda Joubert, Marike Cockeran, Incidence patterns of childhood cancer in two tertiary hospitals in Ghana from 2015 to 2019: A retrospective observational study, Cancer Epidemiology, Volume 87, 2023, 102470, ISSN 1877-7821, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2023.102470. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877782123001509)

- Mohammed A, Aliyu HO. Childhood cancers in a referral hospital in northern Nigeria. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2009 Jul;30(3):95-8. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.64253. PMID: 20838544; PMCID: PMC2930295.

- Klemencic, Sarah & Perkins, Jack. (2019). Diagnosis and Management of Oncologic Emergencies. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 20. 316-322. 10.5811/westjem.2018.12.37335.

- Nelson’s textbook of pediatrics 21st edition by Kleigman, Behrman, Jenson and Stanton

- Principles and practice of pediatric oncology 4th edition by Philip.A. Pizzo and David.G. Poplack

- Williams Haematology,6th edition,by Ernest Beutler M.D,etal.

- Zinner SH. Changing epidemiology of infections in patients with neutropenia and cancer: emphasis on gram-positive and resistant bacteria. Clin Infect Dis.1999;29(3):490–4.

- Melendez E, Harper MB. Risk of serious bacterial infection in isolated and unsuspected neutropenia. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):163–7.

- Moon JM, Chun BJ. Predicting the complicated neutropenic fever in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(11):802–6.

- Roland T. Skeel- Handbook of cancer chemotherapy

- Rheingold & Lange, “Oncologic Emergencies”, in Principles & Practice of Pediatric Oncology, eds Pizzo, Poplack.

- Nazemi Emerg Med Clin N Am 27 (2009) 477–495

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Oncologic Metabolic Emergencies

Background

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death among children and adolescents worldwide. Each year, an estimated 400,000 children and adolescents are diagnosed with cancer, and approximately 90,000 deaths occur annually (1).

Alarmingly, around 80% of cancer-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Nigeria, where limited access to early diagnosis, specialized treatment, and supportive care contributes to poorer outcomes. Strengthening healthcare systems in these regions is essential to improve survival rates and reduce the global burden of childhood malignancies.”

Further readings

- World Health Organization. Childhood Cancer. Dec 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer-in-children Accessed Dec 2024.

- Satyanarayana L, Asthana S, Labani S P. Childhood cancer incidence in India: a review of population-based cancer registries. Indian Pediatr. 2014 Mar;51(3):218-20. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0377-0. PMID: 24736911.

- Winifred E. Owusu, Johanita R. Burger, Martha S. Lubbe, Rianda Joubert, Marike Cockeran, Incidence patterns of childhood cancer in two tertiary hospitals in Ghana from 2015 to 2019: A retrospective observational study, Cancer Epidemiology, Volume 87, 2023, 102470, ISSN 1877-7821, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2023.102470. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877782123001509)

- Mohammed A, Aliyu HO. Childhood cancers in a referral hospital in northern Nigeria. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2009 Jul;30(3):95-8. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.64253. PMID: 20838544; PMCID: PMC2930295.

- Klemencic, Sarah & Perkins, Jack. (2019). Diagnosis and Management of Oncologic Emergencies. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 20. 316-322. 10.5811/westjem.2018.12.37335.

- Nelson’s textbook of pediatrics 21st edition by Kleigman, Behrman, Jenson and Stanton

- Principles and practice of pediatric oncology 4th edition by Philip.A. Pizzo and David.G. Poplack

- Williams Haematology,6th edition,by Ernest Beutler M.D,etal.

- Zinner SH. Changing epidemiology of infections in patients with neutropenia and cancer: emphasis on gram-positive and resistant bacteria. Clin Infect Dis.1999;29(3):490–4.

- Melendez E, Harper MB. Risk of serious bacterial infection in isolated and unsuspected neutropenia. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):163–7.

- Moon JM, Chun BJ. Predicting the complicated neutropenic fever in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(11):802–6.

- Roland T. Skeel- Handbook of cancer chemotherapy

- Rheingold & Lange, “Oncologic Emergencies”, in Principles & Practice of Pediatric Oncology, eds Pizzo, Poplack.

- Nazemi Emerg Med Clin N Am 27 (2009) 477–495

Advertisement