Author's details

- Dr. Jolayemi Waliyat. A

- (MBBS, MPH-Epid, FWACS, FMCOG)

- Consultant Obstetrician and Gynecologist. Evercare Hospital Lekki, Lagos, Nigeria.

Reviewer's details

- Dr Adeboje-Jimoh Fatimah. O

- (FMCOG)

- Lagos University Teaching Hospital)

- Date Uploaded: 2024-07-31

- Date Updated: 2025-12-18

Ectopic Pregnancy

Key Messages

- Ectopic pregnancy is a life-threatening condition where the embryo implants outside the uterine cavity, most often in the fallopian tube, and is a leading cause of maternal mortality, especially with late presentation.

- Early diagnosis relies on clinical history, physical examination, and prompt use of transvaginal ultrasound and β-hCG testing.

- Management options include expectant, medical (methotrexate), and surgical approaches, chosen based on patient stability and clinical scenario.

- Prevention focuses on reducing risk factors such as pelvic infections, limiting sexual partners, and encouraging early medical evaluation for missed periods.

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is defined as a pregnancy in which the implantation of the embryo occurs outside the uterine cavity, most frequently in one of the two fallopian tubes or, more rarely, in the abdominal cavity. It is a common life-threatening gynecological emergency with significant morbidity and mortality especially in developing countries where majority of the patients present late with ruptured form and hemodynamic instability. During the first three months of pregnancy, EP is the leading cause of maternal death in industrialized countries, and possibly the second most frequent cause in developing countries (after abortion complications). Most ectopic pregnancies occur in women aged 25-34 years.

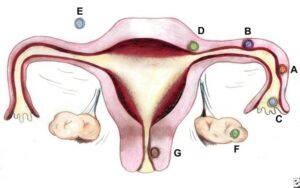

The commonest site of Ectopic Pregnancies is the fallopian tube which accounts for 95 percent of ectopic pregnancies: 55 percent in the ampulla; 20 percent in the isthmus; 17 percent in the fimbria; 2-4 percent in the interstitial. Other sites are the cornual part of the uterus, abdominal cavity, ovary, cervix, broad ligament and rudimentary horn. The right tube is more frequently affected probably as a result of appendicular inflammation.

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy varies among different countries, in same geographical region depending on the prevailing risk factors. In Nigeria, it ranges between 1.1-3.8% of deliveries compared to a rate of 11 per 1000 pregnancies in the UK and 19.6 per 1000 pregnancies in North America. There has been a gradual increase over the years, probably as a true reflection of the larger number of cases in the population or because of improved sensitivity of diagnostic tests for ectopic pregnancy.

Aetiological factors include history of multiple sexual partners and pelvic infections particularly with Chlamydia infection6, as well as history of previous ectopic pregnancy, IUCD or sterilization failure with a reported risk of 7 per 1000 in patients with pregnancies following sterilization procedures.Other associated aetiological factors include previous pelvic or tubal surgery, gross pelvic pathology such as endometriosis, congenital abnormalities of the tubes such as diverticula, accessory Ostia, hypoplasia, in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure.A history of previous induced abortion or infertility and current smoking increase risk.Contraceptive use reduces the annual risk for intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy; however, previous intrauterine device use may increase risk.Other causes include oral progestin-only contraceptive, pelvic adhesion and in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer.

Sites and frequencies of ectopic pregnancy. By Donna M. Peretin, RN. (A) Ampullary (B) Isthmic (C) Fimbrial (D) Cornual/Interstitial; (E) Abdominal(F) Ovarian; and (G) Cervical.

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is complicated by the wide spectrum of clinical presentations, from asymptomatic (especially in early un-ruptured cases) to acute abdomen and hemodynamic shock. Symptoms patient with ectopic pregnancy present with includes amenorrhoea, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, nausea,vomiting, dizziness/fainting attacks, body weakness, abdominal swelling. The classic symptom Triad of lower abdominal pain, amenorrhoea, and vaginal bleeding is present in only about 50% of patients and is most typical in patients in whom an ectopic pregnancy has ruptured. Abdominal pain is the most common presenting complaint as seen in different studies across Nigeria ranging from 80-90.7%. The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in reproductive age woman most times is based on clinical history which should be followed by an attentive physical examination. Evaluation of vital signs to assess for tachycardia and hypotension is pivotal in determining the patient’s hemodynamic stability. When examining the abdomen and suprapubic regions, attention should focus on the location of tenderness as well as any exacerbating factors. If voluntary/involuntary guarding of the abdominal musculature is elicited on palpation, this should raise concern for possible free fluid or other cause of peritoneal signs. Palpating a gravid uterus may suggest pregnancy, however, does not exclude other pathologies such as progressed ectopic pregnancy or heterotopic pregnancy. Patient’s presenting with vaginal bleeding would likely benefit from a pelvic examination to assess for infections as well as assess the cervical os. Bimanual pelvic examination additionally allows for palpation of bilateral adnexa to assess for any abnormal masses/structures or to elicit adnexal tenderness. A thorough history and physical examination will lend better certainty with testing obtained when evaluating for possible ectopic pregnancy.

The importance of ectopic pregnancy in developing countries and Nigeria, in particular, lies in the fact that, while the trend of early diagnosis and conservative treatment is prevalent in developed countries; we are still challenged by late presentations with the ruptured form of the ectopic pregnancy seen in more than 80% of cases [16].

Important differential diagnoses to consider with ectopic pregnancies are ovarian torsion, Tubo-ovarian abscess, appendicitis, hemorrhagic corpus luteum, ovarian cyst rupture, threatened miscarriage, incomplete miscarriage, pelvic inflammatory disease, spontaneous abortion and ureteral calculi.

Early diagnosis and treatment of this condition reduces maternal morbidity and mortality.

Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy start from taking a short and concise clinical history, detailed physical, abdominal and pelvic examination. Investigations useful in aiding the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy include Beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotrophin, Ultrasonography and Laparoscopy.

In female patient presenting to the hospital with amenorrhoea, the first test to do is pregnancy test to check for B-hCG either in urine or serum, once it is positive, the next is to do an ultrasound of the pelvis preferably using the transvaginal route to locate where the gestational sac is. Prompt transvaginal ultrasound evaluation is key in diagnosing ectopic pregnancy. In the face of an equivocal ultrasound result I.e. where the result is not conclusive, it should be combined with quantitative beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin levels12. If a patient has a beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin level of 1,500 mIU per mL or greater, but the transvaginal ultrasonography does not show an intrauterine gestational sac or level is between 6000-6500 mIU per ml and transabdominal ultrasonography doesn’t show an intrauterine gestational sac, ectopic pregnancy should be suspected.

Laparoscopy can function as both investigative tool as well as a treatment option. It used to be the goal standard in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy but since there is improved technology in the area of ultrasonography, transvaginal USS now stands as an important diagnostic tool in patients with ectopic pregnancy. TVS is readily available in most developing countries, not expensive and expertise in its use as against laparoscopy that is not within the reach of the poor. Other ancillary tests are Full blood count, Liver function test, Kidney function test, Group and cross-matching of blood.

Therapeutic management of ectopic pregnancy include: Expectant management, Medical management and Surgical management.

Expectant management

Candidates for successful expectant management should be asymptomatic and have no evidence of rupture or hemodynamic instability. Candidates should demonstrate objective evidence of resolution (eg, declining β-HCG levels).Close follow-up and patient compliance are of paramount importance, as tubal rupture may occur despite low and declining serum levels of β-HCG.

Medical management with Methotrexate

Methotrexate is the standard medical treatment for un-ruptured ectopic pregnancy. A single-dose IM injection is the more popular regimen. The ideal candidate should have the following: Hemodynamic stability, No severe or persisting abdominal pain, The ability to follow up multiple times, Normal baseline liver and renal function test results. Absolute contraindications to methotrexate therapy include the following: Existence of an intrauterine pregnancy, Immunodeficiency, Moderate to severe anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia, Sensitivity to methotrexate, Active pulmonary or peptic ulcer Disease, Clinically important hepatic or renal dysfunction, Breastfeeding and Evidence of tubal rupture.

Other agents that had been evaluated include prostaglandin F2ά, hyperosmolar glucose, hypertonic saline and potassium chloride.

Surgical management

Before the advent of laparoscopy, laparotomy with salpingectomy (removal of the fallopian tube through an abdominal incision) was the standard therapy for managing ectopic pregnancy. Laparoscopy has become the recommended surgical approach in most cases. Laparotomy is usually reserved for patients who are hemodynamically unstable or for patients with cornual ectopic pregnancies; it also is a preferred method for surgeons inexperienced in laparoscopy and in patients in whom a laparoscopic approach is difficult. Laparoscopy with salpingostomy, without fallopian tube removal is also a method of surgical treatment. Laparoscopy has similar tubal patency and future fertility rates as medical treatment. The risk of recurrent ectopic pregnancy is 12-18%, with the future risk increasing further with every successive occurrence.

The follow up in patients managed for ectopic pregnancy depends on the treatment option used. For patients who were managed expectantly or with methotrexate should go to the hospital for quantitative β-HCG measurement every 48hours because the doubling time for this in normal pregnancy is 48hours, this is to ensure that treatment option chosen is working out or if there is need for another option. Those who had their ectopic pregnancy managed surgically should go for follow up 2-3weeks after for repeat test to rule out persistence of the β-HCG in them.

Following an ectopic pregnancy, it is pertinent to counsel the patient appropriately on the chances of recurrence and the need to present early for pregnancy localization in her next pregnancy.

There is no way ectopic pregnancy can be prevented, however, the risk factors to having ectopic pregnancy can be reduced.Such as reducing/limiting the number of sexual partners, preventing sexually transmitted infections or prompt treatment once contracted to reduce damage to the fallopian tubes, using barrier contraception such as condom to reduce the risk of STI/PID,quit smoking, early presentation to hospital once a female in reproductive age missed her menses for testing.

Ectopic pregnancy is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Early diagnosis through ultrasound and prompt intervention are critical to prevent life-threatening complications such as rupture and internal bleeding. Limited access to healthcare and diagnostic tools in rural areas often delays diagnosis, increasing the risks. Improving awareness, enhancing healthcare infrastructure, and ensuring timely surgical or medical management can significantly reduce mortality associated with ectopic pregnancy in the region.

A 28-year-old woman from a rural village in Northern Nigeria, presented with severe lower abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding after missing her period for six weeks. She had a history of untreated pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which likely contributed to her current condition. An ultrasound revealed a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and despite initial stabilization at a local clinic, she required urgent surgery at a regional hospital due to the lack of nearby medical facilities. After a delayed transfer, Amina underwent emergency surgery to remove a ruptured fallopian tube and recovered slowly, facing ongoing challenges related to access to healthcare.

- Audu LR, Ekele BA. A ten year review of maternal mortality in Sokoto, Northern Nigeria. WAJM 2002; 21(1): 74 – 76.

- Ola ER, Imosemi DO, Egwatu J I, Abudu O.O. Ectopic Pregnancy: Lagos University Teaching Hospital experience over a five-year period, Nig Qt J Hosp Med 1990; 9(2):100 – 103.

- Mark AD, John AR. Ectopic pregnancy In: Te Lindes operative Monga A. (ed.) Disorders of early pregnancy. Tenth edition. John AR, Howard WJ. (eds.) Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia. 2008 Pp. 798-824.

- Oloyode OAO, Lamina MA, Odusuga OL, Adetuye PO, Olatunji AO, Fakoya TA, Sule-Odu AO, Jagun OE. Ectopic Pregnancy in Sagamu, a 12 year review. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 2002; 19(2) 34.

- Olatunbosun OA., Okonofua FE: Ectopic pregnancy. The African Experience –Postgraduate Doctor – Africa. 1996; 8(3): Pp. 74-78.

- Davor J. Ectopic pregnancy. In: Edmonds DK (ed.) Dewhurst’s textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for Postgraduates. 7th ed. Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford. 2007 : Pp. 106-16.

- RCOG 2004. Why mothers die 2000-2002. The sixth report of the confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. 2000-2002. London: RCOG press.

- Orji EO, Fasubaa OB, Adeyemi B, Dare FO, Onwudiegwu U, Ogunniyi SO. Mortality and morbidity associated with misdiagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in a defined Nigerian population. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 Sep; 22(5): Pp. 548-50.

- Swende TZ, Jogo AA. Ruptured tubal pregnancy in markurdi, north central Nigeria. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008. Jan-Mar; 17(1): Pp. 75-7.

- Onwuhafua PI, Onwuhafua A, Adesiyun GA, Adze J. Ectopic pregnancies at the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Kaduna, Northern Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2001; 18(2): 82 – 86.

- Hajenius PJ, Mol BWJ, Bossuyi PMM, Ankum WM, Van der Veen F. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2 2003. Oxford: Update software\

- Patrick Thonnean et al. Ectopic pregnancy in Conakry, Guinea, Bull World Health Organ vol. 80 no. 5 2002

- Verema T Valley. Ectopic pregnancy. eMedicine Specialities 2005.

- Anne-Marie L, Beth Potter. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam physician. 2005; 72(9): 1707 – 1714.

- Bouyer J, Job-Spiral N, Pouly JL 1996, Fertility after ectopic pregnancy- results of the first three years of the Auvergne register. Contracept Fertil Sex 24, Pp. 475-81

More topics to explore

Author's details

- Dr Jolayemi

Reviewer's details

- TBD

Ectopic Pregnancy

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is defined as a pregnancy in which the implantation of the embryo occurs outside the uterine cavity, most frequently in one of the two fallopian tubes or, more rarely, in the abdominal cavity. It is a common life-threatening gynecological emergency with significant morbidity and mortality especially in developing countries where majority of the patients present late with ruptured form and hemodynamic instability. During the first three months of pregnancy, EP is the leading cause of maternal death in industrialized countries, and possibly the second most frequent cause in developing countries (after abortion complications). Most ectopic pregnancies occur in women aged 25-34 years.

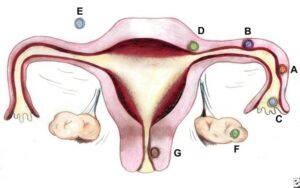

The commonest site of Ectopic Pregnancies is the fallopian tube which accounts for 95 percent of ectopic pregnancies: 55 percent in the ampulla; 20 percent in the isthmus; 17 percent in the fimbria; 2-4 percent in the interstitial. Other sites are the cornual part of the uterus, abdominal cavity, ovary, cervix, broad ligament and rudimentary horn. The right tube is more frequently affected probably as a result of appendicular inflammation.

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy varies among different countries, in same geographical region depending on the prevailing risk factors. In Nigeria, it ranges between 1.1-3.8% of deliveries compared to a rate of 11 per 1000 pregnancies in the UK and 19.6 per 1000 pregnancies in North America. There has been a gradual increase over the years, probably as a true reflection of the larger number of cases in the population or because of improved sensitivity of diagnostic tests for ectopic pregnancy.

Aetiological factors include history of multiple sexual partners and pelvic infections particularly with Chlamydia infection6, as well as history of previous ectopic pregnancy, IUCD or sterilization failure with a reported risk of 7 per 1000 in patients with pregnancies following sterilization procedures.Other associated aetiological factors include previous pelvic or tubal surgery, gross pelvic pathology such as endometriosis, congenital abnormalities of the tubes such as diverticula, accessory Ostia, hypoplasia, in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure.A history of previous induced abortion or infertility and current smoking increase risk.Contraceptive use reduces the annual risk for intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy; however, previous intrauterine device use may increase risk.Other causes include oral progestin-only contraceptive, pelvic adhesion and in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer.

Sites and frequencies of ectopic pregnancy. By Donna M. Peretin, RN. (A) Ampullary (B) Isthmic (C) Fimbrial (D) Cornual/Interstitial; (E) Abdominal(F) Ovarian; and (G) Cervical.

- Audu LR, Ekele BA. A ten year review of maternal mortality in Sokoto, Northern Nigeria. WAJM 2002; 21(1): 74 – 76.

- Ola ER, Imosemi DO, Egwatu J I, Abudu O.O. Ectopic Pregnancy: Lagos University Teaching Hospital experience over a five-year period, Nig Qt J Hosp Med 1990; 9(2):100 – 103.

- Mark AD, John AR. Ectopic pregnancy In: Te Lindes operative Monga A. (ed.) Disorders of early pregnancy. Tenth edition. John AR, Howard WJ. (eds.) Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia. 2008 Pp. 798-824.

- Oloyode OAO, Lamina MA, Odusuga OL, Adetuye PO, Olatunji AO, Fakoya TA, Sule-Odu AO, Jagun OE. Ectopic Pregnancy in Sagamu, a 12 year review. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 2002; 19(2) 34.

- Olatunbosun OA., Okonofua FE: Ectopic pregnancy. The African Experience –Postgraduate Doctor – Africa. 1996; 8(3): Pp. 74-78.

- Davor J. Ectopic pregnancy. In: Edmonds DK (ed.) Dewhurst’s textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for Postgraduates. 7th ed. Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford. 2007 : Pp. 106-16.

- RCOG 2004. Why mothers die 2000-2002. The sixth report of the confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. 2000-2002. London: RCOG press.

- Orji EO, Fasubaa OB, Adeyemi B, Dare FO, Onwudiegwu U, Ogunniyi SO. Mortality and morbidity associated with misdiagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in a defined Nigerian population. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 Sep; 22(5): Pp. 548-50.

- Swende TZ, Jogo AA. Ruptured tubal pregnancy in markurdi, north central Nigeria. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008. Jan-Mar; 17(1): Pp. 75-7.

- Onwuhafua PI, Onwuhafua A, Adesiyun GA, Adze J. Ectopic pregnancies at the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Kaduna, Northern Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2001; 18(2): 82 – 86.

- Hajenius PJ, Mol BWJ, Bossuyi PMM, Ankum WM, Van der Veen F. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2 2003. Oxford: Update software\

- Patrick Thonnean et al. Ectopic pregnancy in Conakry, Guinea, Bull World Health Organ vol. 80 no. 5 2002

- Verema T Valley. Ectopic pregnancy. eMedicine Specialities 2005.

- Anne-Marie L, Beth Potter. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam physician. 2005; 72(9): 1707 – 1714.

- Bouyer J, Job-Spiral N, Pouly JL 1996, Fertility after ectopic pregnancy- results of the first three years of the Auvergne register. Contracept Fertil Sex 24, Pp. 475-81

Content

Author's details

- Dr Jolayemi

Reviewer's details

- TBD

Ectopic Pregnancy

Background

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is defined as a pregnancy in which the implantation of the embryo occurs outside the uterine cavity, most frequently in one of the two fallopian tubes or, more rarely, in the abdominal cavity. It is a common life-threatening gynecological emergency with significant morbidity and mortality especially in developing countries where majority of the patients present late with ruptured form and hemodynamic instability. During the first three months of pregnancy, EP is the leading cause of maternal death in industrialized countries, and possibly the second most frequent cause in developing countries (after abortion complications). Most ectopic pregnancies occur in women aged 25-34 years.

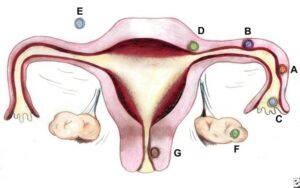

The commonest site of Ectopic Pregnancies is the fallopian tube which accounts for 95 percent of ectopic pregnancies: 55 percent in the ampulla; 20 percent in the isthmus; 17 percent in the fimbria; 2-4 percent in the interstitial. Other sites are the cornual part of the uterus, abdominal cavity, ovary, cervix, broad ligament and rudimentary horn. The right tube is more frequently affected probably as a result of appendicular inflammation.

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy varies among different countries, in same geographical region depending on the prevailing risk factors. In Nigeria, it ranges between 1.1-3.8% of deliveries compared to a rate of 11 per 1000 pregnancies in the UK and 19.6 per 1000 pregnancies in North America. There has been a gradual increase over the years, probably as a true reflection of the larger number of cases in the population or because of improved sensitivity of diagnostic tests for ectopic pregnancy.

Aetiological factors include history of multiple sexual partners and pelvic infections particularly with Chlamydia infection6, as well as history of previous ectopic pregnancy, IUCD or sterilization failure with a reported risk of 7 per 1000 in patients with pregnancies following sterilization procedures.Other associated aetiological factors include previous pelvic or tubal surgery, gross pelvic pathology such as endometriosis, congenital abnormalities of the tubes such as diverticula, accessory Ostia, hypoplasia, in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure.A history of previous induced abortion or infertility and current smoking increase risk.Contraceptive use reduces the annual risk for intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy; however, previous intrauterine device use may increase risk.Other causes include oral progestin-only contraceptive, pelvic adhesion and in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer.

Sites and frequencies of ectopic pregnancy. By Donna M. Peretin, RN. (A) Ampullary (B) Isthmic (C) Fimbrial (D) Cornual/Interstitial; (E) Abdominal(F) Ovarian; and (G) Cervical.

Further readings

- Audu LR, Ekele BA. A ten year review of maternal mortality in Sokoto, Northern Nigeria. WAJM 2002; 21(1): 74 – 76.

- Ola ER, Imosemi DO, Egwatu J I, Abudu O.O. Ectopic Pregnancy: Lagos University Teaching Hospital experience over a five-year period, Nig Qt J Hosp Med 1990; 9(2):100 – 103.

- Mark AD, John AR. Ectopic pregnancy In: Te Lindes operative Monga A. (ed.) Disorders of early pregnancy. Tenth edition. John AR, Howard WJ. (eds.) Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia. 2008 Pp. 798-824.

- Oloyode OAO, Lamina MA, Odusuga OL, Adetuye PO, Olatunji AO, Fakoya TA, Sule-Odu AO, Jagun OE. Ectopic Pregnancy in Sagamu, a 12 year review. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol, 2002; 19(2) 34.

- Olatunbosun OA., Okonofua FE: Ectopic pregnancy. The African Experience –Postgraduate Doctor – Africa. 1996; 8(3): Pp. 74-78.

- Davor J. Ectopic pregnancy. In: Edmonds DK (ed.) Dewhurst’s textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for Postgraduates. 7th ed. Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford. 2007 : Pp. 106-16.

- RCOG 2004. Why mothers die 2000-2002. The sixth report of the confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. 2000-2002. London: RCOG press.

- Orji EO, Fasubaa OB, Adeyemi B, Dare FO, Onwudiegwu U, Ogunniyi SO. Mortality and morbidity associated with misdiagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in a defined Nigerian population. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 Sep; 22(5): Pp. 548-50.

- Swende TZ, Jogo AA. Ruptured tubal pregnancy in markurdi, north central Nigeria. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008. Jan-Mar; 17(1): Pp. 75-7.

- Onwuhafua PI, Onwuhafua A, Adesiyun GA, Adze J. Ectopic pregnancies at the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Kaduna, Northern Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2001; 18(2): 82 – 86.

- Hajenius PJ, Mol BWJ, Bossuyi PMM, Ankum WM, Van der Veen F. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2 2003. Oxford: Update software\

- Patrick Thonnean et al. Ectopic pregnancy in Conakry, Guinea, Bull World Health Organ vol. 80 no. 5 2002

- Verema T Valley. Ectopic pregnancy. eMedicine Specialities 2005.

- Anne-Marie L, Beth Potter. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam physician. 2005; 72(9): 1707 – 1714.

- Bouyer J, Job-Spiral N, Pouly JL 1996, Fertility after ectopic pregnancy- results of the first three years of the Auvergne register. Contracept Fertil Sex 24, Pp. 475-81

Advertisement