Author's details

- Dr Bello Afeez Oyesola

- MBBS, FMCPaed, MPH.

- Federal Medical Centre, Bida, Niger State

Reviewer's details

- Ameen-Ikoyi, Ibrahim

- FWACP

- (paediatrics) Emel Hospital, Lagos Nigeria.

- Date Uploaded: 2024-08-23

- Date Updated: 2025-12-20

Childhood seizure disorder (Epilepsy)

Key Messages

- Childhood seizures are often due to abnormal brain activity, with causes including genetic syndromes, brain malformations, infections, and perinatal complications; over half have no known cause.

- Diagnosis relies on detailed history, physical examination, and investigations like EEG and neuroimaging to classify seizure types and identify underlying lesions.

- Management involves a multidisciplinary team, with antiepileptic drugs as the mainstay; monotherapy is preferred, and options are chosen based on seizure type.

- Preventive strategies include injury prevention, maternal health, vaccination, hygiene, and strengthening primary healthcare.

Seizure is a manifestation of abnormal excessive synchronous discharge of neurons primarily in the cerebral cortex. Children are more prone to seizure mainly due to immature brain particularly in infants. When seizures are focal, it is due to involvement of a restricted region at onset. Epilepsy refers to two or more unprovoked seizures that occurred > 24 hours apart. In the presence of a focal lesion, one episode of seizure maybe labeled as epilepsy, as this increases the probability of recurrent seizures. Epilepsy is seen as unprovoked seizures with neurologic, cognitive, psychologic and social consequences. Globally, 0.5% of children suffer some form of seizure during childhood. Though 70% of seizures occur in children and the burden is worse in developing countries especially sub-Saharan Africa, there is paucity of data on the burden and the pattern in this population. This is because of the challenge with keeping a seizure registry, most of the patients default from clinic after sometime. Also most of them especially in the rural area seek other forms of non-conventional care instead of presenting in the hospitals.

Seizure occurs when a sudden imbalance occurs between excitatory and inhibitory forces within the network of cortical neurons in favour of sudden net excitation. It occurs due to one of increased activation, decreased inhibition of neurons, also due to defective activation of gama aminobutyric acid (GABA) and involvement of thalamocortical rhythms / circuits in the brain. The brain is involved in almost all bodily function and when this abnormality occurs manifestations are variable, ranging from sensory, motor, psychic, autonomic, gustatory etc.

More than 50% of seizures have no known aetiology. Causes that are well elucidated are post-infection, inherited syndromes, congenital brain malformation and syndromes. These aetiologies are interwoven with syndromes occurring due to chromosomal, metabolic, mitochondrial and single gene mutations. Common genetic syndromes manifesting with seizure disorder include tuberous sclerosis, Sturge weber, Rett, Prader Willi etc. Some mutations such as SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN1B have been associated with febrile seizures. Complex types of febrile seizures have the risk of resulting in epilepsy. In low and middle income countries (LMICs) neonatal conditions such as severe perinatal asphyxia, bilirubin encephalopathy, severe acute malnutrition and acute febrile illnesses (severe malaria, meningitis etc) all predispose to cerebral palsy with seizure disorders.

History taking is very important and identifying whether seizure occurred or not is important. History also on nature of seizure and complications associated with it. All these information are best given by eye witness and not only the caregiver. Children above 5 years will assist with information regarding history of aura, preservation of consciousness and postictal state. Other important history include what precipitated seizure, its duration and interventions during and after seizure. Physical examination for neuro-cutaneous disorders and other disorders is equally important.

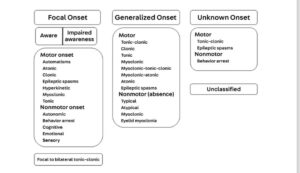

Seizure classification was first done in 1970 by the International classification of epileptic seizures (ILAE), it was updated in 1981 and 1989. The most recent update was in 2017 and this is presented below (Table I):

Epilepsy syndromes also occur, some examples are juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, benign neonatal familial convulsions, Ortahara syndrome, west syndrome, Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, benign Rolandic epilepsies and status epilepticus.

Identifying some conditions such as breath-holding spells, narcolepsy, cataplexy, syncope, benign paroxysmal vertigo, panic attack, tics, spasmus nutans, benign paroxysmal torticollis, migraine with visual aura and jitteriness usually limit confusing these conditions with epilepsy.

Fig: This is ILAE 2017 classification of seizures.

Specific investigations aim to identify focal lesions and properly classify the seizure type. A high index of suspicion will allow quick identification of seizure aetiology and other investigations that are appropriate. Neuro-imaging is necessary when there are focal or lateralizing signs. The investigations applicable in this regard are:

Brain magnetic resonance image (MRI)

Brain computer tomography scan (CT-Scan)

They may show lesions in the brain that may benefit from surgical intervention. This may just relieve seizures.

Electroencephalogram helps in identifying type of seizure. It also helps in prognosticating, guides selection of medications and when to discontinue medications. Findings on EEG may include:

- Abnormal epileptiform discharge

- Diffuse background slowing

- Focal slowing

- Intermittent diffuse intermixed slowing.

- Hypsarrhythmia

- Polyspikes and wave discharge.

Treatment for seizure disorder requires multi-specialist care. With family Physicians, Paediatric Neurologist, Neurosurgeons, Psychologist, Mental Health Physicians and Physiotherapist all having a role to play. Early identification of seizure and its proper classification enhances appropriate treatment for epilepsy. Anticonvulsant is the mainstay of epilepsy treatment, the seizure type/ syndromes helps in deciding which antiepileptic is most appropriate. Monotherapy is preferred because it is less expensive, it limits adverse events and drug-drug interactions. Below is a table of common anti-epileptic medications (Table II).

Ketogenic diet: This aims at achieving ketosis and ketonuria which will result in control of seizure. It could be applied in children 3-15years but common side effects are abdominal pains, vomiting and diarrhea.

Surgical treatment: This is of use in intractable seizures. It becomes a prominent mode of management when seizure is refractory. Certain conditions are usually fulfilled before considering this option.

Table I: Common antiepileptic agents for children

| Medication | Common side-effect | Dosage | Useful for what seizure |

| Carbamazepine | High drug-drug interaction | 10-35mg/kg | Generalized clonic tonic seizure and partial seizure |

| Lamotrigine | Rash and nausea | 1-5mg/kg | Generalized and partial seizure |

| Levetiracetam | Fatigue and somnolence | 10 -40mg/kg | Primary generalized seizure and partial seizure |

| Topiramate | Weight loss and mood changes | 1-3mg/kg | Generalized and partial seizure |

| Valproate | 10-60mg/kg | Most seizure types including Myoclonic | |

| Barbiturates | Dizziness, poor concentration | 2.5-8mg/kg | Generalized convulsion and status epilepticus |

| Phenytoin | Osteopaenia and cerebellar ataxia | 5-10mg/kg | Partial, generalized and mixed seizure |

| Ethosuximide | Hyperactivity and sleep disturbance | 20-40mg/kg | Absence and Myoclonic seizure |

| Primidone | Sedation, drowsiness and fatigue | Focal and psychomotor |

No single approach will prevent epilepsy. However, general healthy living and implementing policies that strengthen health systems especially those relating to public health may contribute in reducing epilepsy burden. Some recognized interventions include:

- Preventing head injury by using head gears / helmets and seat belts

- Staying healthy during pregnancy

- Ensuring strict compliance to the vaccination regimen in children.

- Hand and food hygiene

- Strengthening primary health care services.

Childhood seizure disorders in sub-Saharan Africa present significant challenges due to limited access to healthcare, diagnostic tools, and appropriate treatment. Early recognition and management are critical to improving outcomes, but barriers such as stigma, traditional beliefs, and scarcity of antiepileptic medications hinder effective care. Strengthening healthcare systems, increasing awareness, and improving access to diagnosis and treatment are essential to reducing the burden of childhood seizure disorders in the region.

A 4 year old boy was referred from the general outpatient clinic on account of recurrent history of seizure in last 3 years. Seizure was first noticed when he was 13 months old, each episode lasted 2-5minutes, involved all the limbs. It was associated with eye rolling and sudden loss of posture . He initially had 1-3 episode weekly, but later worsened to 1-2 episodes daily, though the seizure characteristics remained same. No aura prior to episodes, no fever or pain in any part of the body.

He was delivered at home and mother volunteered that he was spanked severally before crying. He was not taken to hospital after delivery. Since onset of seizures , parents have visited patent medicine store and traditionalist. All interventions they gave had no significant positive effect on him. On examination, he was not pale, not jaundiced and not in respiratory distress, he was afebrile (36.7C). Central nervous system exam revealed an hemiplegic gait, and tone was increased in the lower limbs. No signs of meningeal irritation and speech was slurred. Other systems were normal. A diagnosis of Generalized tonic clonic seizures with background spastic cerebral palsy was made.

He was asked to do electro-encephalogram, brain magnetic resonance imaging. He was referred to the Physiotherapist , and commenced on oral carbamazepine @ 15mg/kg in two divided doses. Parents were counselled especially on home care for a convulsing child. He was given a 2 weeks appointment at the paediatric neurology clinic.

- Azubuike JC, Nkanginieme KEO, Ezechukwu C, Nte AR, Adedoyin OT (Ed). Iloeje SO and Ojinnaka N. Paediatrics and child health in a tropical region 2016. Educational printing and publishing, Lagos, Nigeria 3rd Edition. Pg 1158 – 1182.

- Birbeck GL, French JA, Perucca E, Simpson DA, Fraimuo H, George JM et al. Antiepileptic drug selection for people with HIV/AIDs evidence based guideline from ILAE and AAN. Epilepsia 2012. 53 (1): 207 – 214.

- Lagunju I, Fatunde OJ, Takon JQ. Profile of childhood epilepsy in Nigeria. Journal of paediatric neurology 2009. 7(2): 135 – 140. doi.10.3233/JPN_2009-0277

- Mastrngelo M and Leuzzi V. Genes of early onset epileptic encephalopathies: from genotype to phenotype. Paediatr Neurol 2012. 46 (1): 24 – 31.

- Ramos-Lizena J, Rodriguez-Lucenilla MI, Aguilera-Lopen P, Aguirre-Rodriguez J, Cassinello-Garcia A. A study of drug resistant childhood epilepsy testing the new ILAE criteria. Seizure 2012. 21(4): 266 – 272.

- David YK. Epilepsy and seizure. Medscape 2024. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com. Assessed on 9th October 2024.

- Pack A.M. Epilepsy overview and revised classification of seizures and epilepsies. CONTINUUM (MINNEAP MINN)2019;25(2, EPILEPSY):306–321.

- Fine A, Wirrell E.C. Seizures in children. Pedsinreview 2020; 41(7)

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Childhood seizure disorder (Epilepsy)

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

Seizure is a manifestation of abnormal excessive synchronous discharge of neurons primarily in the cerebral cortex. Children are more prone to seizure mainly due to immature brain particularly in infants. When seizures are focal, it is due to involvement of a restricted region at onset. Epilepsy refers to two or more unprovoked seizures that occurred > 24 hours apart. In the presence of a focal lesion, one episode of seizure maybe labeled as epilepsy, as this increases the probability of recurrent seizures. Epilepsy is seen as unprovoked seizures with neurologic, cognitive, psychologic and social consequences. Globally, 0.5% of children suffer some form of seizure during childhood. Though 70% of seizures occur in children and the burden is worse in developing countries especially sub-Saharan Africa, there is paucity of data on the burden and the pattern in this population. This is because of the challenge with keeping a seizure registry, most of the patients default from clinic after sometime. Also most of them especially in the rural area seek other forms of non-conventional care instead of presenting in the hospitals.

Seizure occurs when a sudden imbalance occurs between excitatory and inhibitory forces within the network of cortical neurons in favour of sudden net excitation. It occurs due to one of increased activation, decreased inhibition of neurons, also due to defective activation of gama aminobutyric acid (GABA) and involvement of thalamocortical rhythms / circuits in the brain. The brain is involved in almost all bodily function and when this abnormality occurs manifestations are variable, ranging from sensory, motor, psychic, autonomic, gustatory etc.

- Azubuike JC, Nkanginieme KEO, Ezechukwu C, Nte AR, Adedoyin OT (Ed). Iloeje SO and Ojinnaka N. Paediatrics and child health in a tropical region 2016. Educational printing and publishing, Lagos, Nigeria 3rd Edition. Pg 1158 – 1182.

- Birbeck GL, French JA, Perucca E, Simpson DA, Fraimuo H, George JM et al. Antiepileptic drug selection for people with HIV/AIDs evidence based guideline from ILAE and AAN. Epilepsia 2012. 53 (1): 207 – 214.

- Lagunju I, Fatunde OJ, Takon JQ. Profile of childhood epilepsy in Nigeria. Journal of paediatric neurology 2009. 7(2): 135 – 140. doi.10.3233/JPN_2009-0277

- Mastrngelo M and Leuzzi V. Genes of early onset epileptic encephalopathies: from genotype to phenotype. Paediatr Neurol 2012. 46 (1): 24 – 31.

- Ramos-Lizena J, Rodriguez-Lucenilla MI, Aguilera-Lopen P, Aguirre-Rodriguez J, Cassinello-Garcia A. A study of drug resistant childhood epilepsy testing the new ILAE criteria. Seizure 2012. 21(4): 266 – 272.

- David YK. Epilepsy and seizure. Medscape 2024. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com. Assessed on 9th October 2024.

- Pack A.M. Epilepsy overview and revised classification of seizures and epilepsies. CONTINUUM (MINNEAP MINN)2019;25(2, EPILEPSY):306–321.

- Fine A, Wirrell E.C. Seizures in children. Pedsinreview 2020; 41(7)

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Childhood seizure disorder (Epilepsy)

Background

Seizure is a manifestation of abnormal excessive synchronous discharge of neurons primarily in the cerebral cortex. Children are more prone to seizure mainly due to immature brain particularly in infants. When seizures are focal, it is due to involvement of a restricted region at onset. Epilepsy refers to two or more unprovoked seizures that occurred > 24 hours apart. In the presence of a focal lesion, one episode of seizure maybe labeled as epilepsy, as this increases the probability of recurrent seizures. Epilepsy is seen as unprovoked seizures with neurologic, cognitive, psychologic and social consequences. Globally, 0.5% of children suffer some form of seizure during childhood. Though 70% of seizures occur in children and the burden is worse in developing countries especially sub-Saharan Africa, there is paucity of data on the burden and the pattern in this population. This is because of the challenge with keeping a seizure registry, most of the patients default from clinic after sometime. Also most of them especially in the rural area seek other forms of non-conventional care instead of presenting in the hospitals.

Seizure occurs when a sudden imbalance occurs between excitatory and inhibitory forces within the network of cortical neurons in favour of sudden net excitation. It occurs due to one of increased activation, decreased inhibition of neurons, also due to defective activation of gama aminobutyric acid (GABA) and involvement of thalamocortical rhythms / circuits in the brain. The brain is involved in almost all bodily function and when this abnormality occurs manifestations are variable, ranging from sensory, motor, psychic, autonomic, gustatory etc.

Further readings

- Azubuike JC, Nkanginieme KEO, Ezechukwu C, Nte AR, Adedoyin OT (Ed). Iloeje SO and Ojinnaka N. Paediatrics and child health in a tropical region 2016. Educational printing and publishing, Lagos, Nigeria 3rd Edition. Pg 1158 – 1182.

- Birbeck GL, French JA, Perucca E, Simpson DA, Fraimuo H, George JM et al. Antiepileptic drug selection for people with HIV/AIDs evidence based guideline from ILAE and AAN. Epilepsia 2012. 53 (1): 207 – 214.

- Lagunju I, Fatunde OJ, Takon JQ. Profile of childhood epilepsy in Nigeria. Journal of paediatric neurology 2009. 7(2): 135 – 140. doi.10.3233/JPN_2009-0277

- Mastrngelo M and Leuzzi V. Genes of early onset epileptic encephalopathies: from genotype to phenotype. Paediatr Neurol 2012. 46 (1): 24 – 31.

- Ramos-Lizena J, Rodriguez-Lucenilla MI, Aguilera-Lopen P, Aguirre-Rodriguez J, Cassinello-Garcia A. A study of drug resistant childhood epilepsy testing the new ILAE criteria. Seizure 2012. 21(4): 266 – 272.

- David YK. Epilepsy and seizure. Medscape 2024. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com. Assessed on 9th October 2024.

- Pack A.M. Epilepsy overview and revised classification of seizures and epilepsies. CONTINUUM (MINNEAP MINN)2019;25(2, EPILEPSY):306–321.

- Fine A, Wirrell E.C. Seizures in children. Pedsinreview 2020; 41(7)

Advertisement