Author's details

- Dr. Afolayan Folake Moriliat

- (MB;BS, MSc Tropical Pediatrics, FMCPaed)

- Consultant pediatrician at Kwara State Teaching Hospital, Ilorin

Reviewer's details

- Dr. Abdurrazzaq Alege

- MBBS, MBA (Healthcare Mgt), FMCPaed, FIPNA Consultant Paediatrician/Paediatric Nephrologist.

- Head, Nephrology/Infectious Diseases Unit. Department of Paedaitrics and Child Health. Federal Teaching Hospital, Katsina Nigeria

- Date Uploaded: 2024-10-12

- Date Updated: 2025-01-27

Acute Kidney Injury in Children

Summary

The understanding of Acute Renal Failure (ARF) has evolved considerably in recent years. Previously, the focus was primarily on severe acute declines in kidney function, characterized by significant azotaemia and often accompanied by oliguria or anuria. However, recent studies indicate that even minor kidney injuries or impairments, reflected by slight changes in serum creatinine (sCr) and/or urine output (UO), can predict serious clinical outcomes.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) describes both functional and structural damage to the kidneys that usually manifest as rapid decline in renal function developing over a few hours to days. It is not just acute renal failure but encompasses the entire spectrum of acute kidney diseases from mild to more severe forms of injury. AKI is characterized by rapid loss of excretory function of the kidneys manifesting as an increase in blood concentration of creatinine and nitrogenous waste product as well as the inability of the kidney to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance. It is a complex syndrome with diverse underlying causes.

Acute Kidney Injury could be classified according to clinical and aetiological considerations into three broad categories.

Pre- renal Kidney Injury is characterized by diminished effective circulating arterial volume with a subsequent decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The reduction in renal perfusion activates auto regulatory mechanisms including increased sympathetic tone, activation of the renin-angiotensin system, release of antidiuretic hormone, and local paracrine activities (prostaglandin release). These regulatory mechanisms restore the renal perfusion in the early phase of the AKI. However, where the underlying cause of the AKI is not corrected or there is continuous loss of intravascular fluids, the pre-renal AKI will progress to ischaemic damage to the kidneys. Common causes of pre-renal AKI include dehydration, sepsis, haemorrhage, malaria, severe hypoalbuminaemia and cardiac failure.

Initiation phase-It is a period at which the kidneys are exposed to an insult resulting in severe cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion that leads to acute cell injury and dysfunction. This is the evolving phase of renal injury. ATN is potentially preventable during this period which may last a few hours to days.

Maintenance phase-This is the phase at which renal parenchyma injury has been established and glomerular filtration rate stabilizes at a value of 5-10mls/min. This phase typically last 1-2 weeks before the recovery phase.

Recovery phase-It is characterized by recovery of renal function through repair and regeneration of renal tissue. Its onset is typically heralded by a gradual increase in urine output and a delayed fall in serum creatinine.

Post- Renal Kidney injury occur as a result of obstruction of the ureter, bladder, or urethra and can cause an increase in fluid pressure proximal to the obstruction. This increase in pressure, in turn, causes renal damage, resulting in decreased renal function. Common causes include congenital abnormalities of the urinary tract such as posterior urethral valves and bilateral ureteropelvic junction obstruction associated with acute obstruction of the urinary tract.

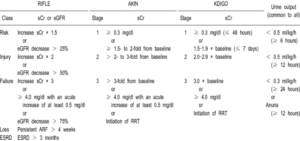

Figure 1; RIFFLE, AKIN AND KDIGO criteria for AKI

At least three different definitions of AKI have been proposed in the last decade. Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) proposed a uniform definition for AKI with acronym RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-Stage Renal Disease) criteria in 2004. This was followed by Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria 2 years later with the intent of increasing the sensitivity of RIFLE classification. The most recent is the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) in 2012 which is a combination of RIFLE AND AKIN criteria as shown in figure 1 above.

The signs and symptoms of acute kidney injury (AKI) can vary depending on the underlying disease. Common clinical findings include pallor (due to anaemia), reduced urine output (oliguria/anuria), oedema (due to salt and water retention), hypertension, vomiting, and lethargy (indicative of uraemic encephalopathy). A detailed patient history can help identify the cause of of the kidney Injury. For example, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever may indicate dehydration and pre-renal azotaemia but could also precede the onset of hemolytic uremic syndrome or renal vein thrombosis. A history of recent skin or throat infections may suggest post-streptococcal acute glomerulonephritis (PSAGN), while a rash could point to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or anaphylactoid purpura. It is also important to investigate any exposure to chemicals or medications. The presence of flank masses may indicate renal vein thrombosis, tumors, cystic diseases, or urinary obstructions.

History and Physical Examination:

- History:

- Recent illness (e.g., gastroenteritis, upper respiratory infection).

- Medication history (e.g., nephrotoxic drugs like NSAIDs, Aminoglycosides).

- Features of malaria, sepsis etc.

- Fluid intake and output.

- Symptoms of urinary tract obstruction (e.g., abdominal pain, urinary retention).

- Physical Examination:

- Vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate).

- Signs of dehydration or fluid overload.

- Oedema.

- Abdominal. examination for masses or bladder distension.

- Skin rash (indicative of systemic diseases).

Laboratory Tests:

1. Blood Tests:

- Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN).

- Electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphate).

- Complete blood count (CBC).

- Blood gas analysis.

- Liver function tests (if indicated).

- Blood cultures (if sepsis is suspected).

3. Urine Tests:

- Urinalysis (including specific gravity, protein, glucose, sediment examination).

- Urine electrolytes (sodium, potassium, creatinine).

- Urine output monitoring (oliguria or anuria).

- Imaging Studies:

- Renal ultrasound to assess kidney size, structure, and presence of obstruction.

- Doppler ultrasound for renal blood flow (if indicated).

- Radionuclide renal scan (e.g., DMSA, MAG3) for functional assessment.

- Other Investigations:

- Renal biopsy (if glomerulonephritis or vasculitis is suspected).

- Serological tests (e.g., ANA, ANCA, complement levels) for autoimmune conditions.

Hypovolaemia Management:

- Volume Expansion: If hypovolaemia is detected, administer isotonic saline intravenously at a dose of 20 ml/kg over 30 minutes.

- Colloid Solutions: In the absence of blood loss or hypoproteinaemia, colloid solutions are not necessary for volume expansion.

Post-Infusion Monitoring: After infusion, the patient should generally void within 2 hours. Failure to void warrants a thorough re-evaluation of the patient.

- Diuretic Therapy: If the patient is adequately hydrated based on clinical and laboratory evaluations, aggressive diuretic therapy may be considered. For oliguric patients, frusemide or mannitol (or both) can increase urine production, which is beneficial for managing hyperkalemia and fluid overload.

- Frusemide Administration: Administer frusemide as a single IV dose of 2 mg/kg at a rate of 4 mg/min. If no response, a second dose of 10 mg/kg may be given. If there is still no increase in urine production, further frusemide therapy is contraindicated.

- Mannitol Administration: A single IV dose of 0.5 g/kg of mannitol can be given over 30 minutes in addition to or instead of frusemide. No additional mannitol should be given due to toxicity risks.

Fluid Restriction:

- Oliguria/Anuria with normal intravascular volume: Limit fluid administration to 400 ml/m²/24 hours for insensible losses plus an amount equal to the urine output of the day.

- Hypervolaemia Patient may require almost total fluid restriction. Use glucose-containing solutions (10-30%) without electrolytes as maintenance fluid, modifying the composition based on the state of electrolyte balance.

Potassium Restriction: Do not administer potassium-containing fluids, food, or medications until adequate renal function is re-established.

- Serum Potassium > 5.5 meq/l: Use sodium polystyrene sulfonate resin (Kayexalate) 1 g/kg orally or by retention enema to exchange sodium for potassium across the colonic mucosa.

Emergency Measures for Serum Potassium > 7 meq/l:

- Calcium Gluconate: 0.5-1.0 ml/kg of 10% solution IV over 10-15 minutes to stabilize membrane potential.

- Sodium Bicarbonate: 1 meq/kg of 7.5% solution IV over 30 minutes to shift potassium into cells.

- Glucose and Insulin: 0.5 g/kg of glucose with 0.1 unit/kg of regular insulin IV over 30 minutes to stimulate cellular uptake of potassium.

- β-agonist (Albuterol): 5-10 mg via nebulizer to stimulate cellular uptake of potassium. Side effects include tachycardia and hypertension.

- Dialysis: For persistent hyperkalemia despite these measures.

Acidosis Management:

- Mild Acidosis: Typically, does not require treatment.

- Severe Acidosis: Correct partially with IV sodium bicarbonate to raise arterial pH to 7.20. (Formula: NaHCO₃ required = 0.3 × weight (kg) × (12 - serum NaHCO₃ (meq/l).

Management of Hyponatraemia

- Fluid Restriction in hyponatraemia resulting from excessive administration of hypotonic fluids. Hypertonic saline can also be considered.

Seizure Management:

- Address any primary disease causing seizures. However, hyponatraemia, hypocalcaemia, hypertension, or uraemia can potentially cause seizure, thus they should be addressed. .Diazepam is effective for seizure control. Other anticonvulsants like paraldehyde, phenobarbitone, and phenytoin are less effective in uraemia.

Anaemia Management:

- Mild Anemia: Typically, due to volume expansion and does not require transfusion unless associated with haemolysis or bleeding.

- Acute Blood Loss: Replace appropriately with slow transfusion (4-6 hour of fresh blood to minimize potassium load. Use packed red cells to prevent hypervolaemia.

Dietary Management:

- Initial Restrictions: Limit to fats and carbohydrates, restricting sodium, potassium, and water.

- Extended Renal Failure: If persisting beyond 7 days, prescribe an expanded oral diet for renal failure. Consider hyperalimentation with essential amino acids.

The purpose of dialysis is to remove toxins and maintain fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance until renal function returns. The methods considered in children include; Peritoneal dialysis, haemodialysis, and hemofiltration. There are several indications for dialysis which include;

Indications for dialysis

- Volume overload with hypertension/pulmonary oedema unresponsive to diuretics

- Persistent hyperkalaemia

- Severe metabolic acidosis unresponsive to medical management

- Neurological symptoms (altered mental state, seizures)

- BUN > 100-150 mg/dl or serum creatinine > 500 μmol/l

- Calcium/phosphorus imbalance with hypocalcaemic tetany

- Pre-Renal Causes: Dehydration, septic shock

- Intrinsic Renal Diseases: Acute tubular necrosis, glomerulonephritis, interstitial nephritis

- Post-Renal Obstruction: Congenital anomalies, kidney stones

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): Consider in patients with a history of growth retardation, anaemia, or other signs of long-standing kidney dysfunction

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Likely Recovery: Renal failure due to prerenal causes, haemolytic uremic syndrome, acute tubular necrosis (ATN), acute interstitial nephritis, or uric acid nephropathy.

Unlikely Recovery: Renal failure from rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis (GMN), bilateral renal vein thrombosis, or bilateral cortical necrosis.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) in children is a serious condition that often goes underdiagnosed in low-income settings due to limited healthcare resources and diagnostic tools. Early identification and treatment are crucial to prevent long-term kidney damage or death. Improving access to clean water, sanitation, and early medical interventions, along with strengthening healthcare systems, can significantly reduce the burden of AKI in children in resource-limited areas.

An 8-year-old boy was brought into the pediatric emergency unit with fever, chills with rigor, vomiting, diarrhea, passage of coke-colored urine, and impaired consciousness. Examination revealed an unconscious child with anaemia and features of heart failure. Bedside investigation revealed a packed cell volume of 22%, a random blood sugar level of 3.0 mg/dl, and a positive rapid diagnostic test for malaria. The child was diagnosed with severe malaria, presenting with severe anaemia, cerebral malaria, and hemoglobinuria. He was commenced on intravenous fluids, artesunate, and transfused with packed red blood cells. Protocols for managing an unconscious child were instituted. Two days after commencing treatment, the child was noticed to be oliguric, with only 65 ml of urine collected in the urine bag over 24 hours. An assessment of malaria-associated acute kidney injury (AKI) was included as part of the severe malaria diagnosis. Biochemical results showed hyponatraemia, hypokalaemia, and elevated creatinine and urea levels.

- Atanda AT, Olowu WA. “Acute kidney injury in Nigeria: Review of a developing country’s perspective.” Pan Afr Med J. 2017.

- Esezobor CI, Ladapo TA, Lesi FE. “Paediatric acute kidney injury in an African setting: prevalence, outcomes and predictors of mortality.” BMC Nephrol. 2014.

- Ibrahim OR, Adamu B, Abdu A. “Acute kidney injury and associated factors in children hospitalized in a tertiary institution in Nigeria.” Niger Med J. 2016.

- Bellomo, R., Kellum, J. A., & Ronco, C. (2012). Acute kidney injury. The Lancet, 380(9843), 756-766.

- KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney International Supplements, 2(1), 1-138.

- Chertow, G. M., Burdick, E., Honour, M., Bonventre, J. V., & Bates, D. W. (2005). Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 16(11), 3365-3370.

- Mehta, R. L., Kellum, J. A., Shah, S. V., Molitoris, B. A., Ronco, C., Warnock, D. G., & Levin, A. (2007). Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Critical Care, 11(2), R31.

- Palevsky, P. M., Liu, K. D., & Brophy, P. D. (2013). KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 61(5), 649-672.

- Hoste, E. A. J., Bagshaw, S. M., Bellomo, R., Cely, C. M., Colman, R., Cruz, D. N., … & Kellum, J. A. (2015). Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Medicine, 41(8), 1411-1423.

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Acute Kidney Injury in Children

- Background

- Symptoms

- Clinical findings

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Treatment

- Follow-up

- Prevention and control

- Further readings

The understanding of Acute Renal Failure (ARF) has evolved considerably in recent years. Previously, the focus was primarily on severe acute declines in kidney function, characterized by significant azotaemia and often accompanied by oliguria or anuria. However, recent studies indicate that even minor kidney injuries or impairments, reflected by slight changes in serum creatinine (sCr) and/or urine output (UO), can predict serious clinical outcomes.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) describes both functional and structural damage to the kidneys that usually manifest as rapid decline in renal function developing over a few hours to days. It is not just acute renal failure but encompasses the entire spectrum of acute kidney diseases from mild to more severe forms of injury. AKI is characterized by rapid loss of excretory function of the kidneys manifesting as an increase in blood concentration of creatinine and nitrogenous waste product as well as the inability of the kidney to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance. It is a complex syndrome with diverse underlying causes.

- Atanda AT, Olowu WA. “Acute kidney injury in Nigeria: Review of a developing country’s perspective.” Pan Afr Med J. 2017.

- Esezobor CI, Ladapo TA, Lesi FE. “Paediatric acute kidney injury in an African setting: prevalence, outcomes and predictors of mortality.” BMC Nephrol. 2014.

- Ibrahim OR, Adamu B, Abdu A. “Acute kidney injury and associated factors in children hospitalized in a tertiary institution in Nigeria.” Niger Med J. 2016.

- Bellomo, R., Kellum, J. A., & Ronco, C. (2012). Acute kidney injury. The Lancet, 380(9843), 756-766.

- KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney International Supplements, 2(1), 1-138.

- Chertow, G. M., Burdick, E., Honour, M., Bonventre, J. V., & Bates, D. W. (2005). Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 16(11), 3365-3370.

- Mehta, R. L., Kellum, J. A., Shah, S. V., Molitoris, B. A., Ronco, C., Warnock, D. G., & Levin, A. (2007). Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Critical Care, 11(2), R31.

- Palevsky, P. M., Liu, K. D., & Brophy, P. D. (2013). KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 61(5), 649-672.

- Hoste, E. A. J., Bagshaw, S. M., Bellomo, R., Cely, C. M., Colman, R., Cruz, D. N., … & Kellum, J. A. (2015). Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Medicine, 41(8), 1411-1423.

Content

Author's details

Reviewer's details

Acute Kidney Injury in Children

Background

The understanding of Acute Renal Failure (ARF) has evolved considerably in recent years. Previously, the focus was primarily on severe acute declines in kidney function, characterized by significant azotaemia and often accompanied by oliguria or anuria. However, recent studies indicate that even minor kidney injuries or impairments, reflected by slight changes in serum creatinine (sCr) and/or urine output (UO), can predict serious clinical outcomes.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) describes both functional and structural damage to the kidneys that usually manifest as rapid decline in renal function developing over a few hours to days. It is not just acute renal failure but encompasses the entire spectrum of acute kidney diseases from mild to more severe forms of injury. AKI is characterized by rapid loss of excretory function of the kidneys manifesting as an increase in blood concentration of creatinine and nitrogenous waste product as well as the inability of the kidney to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance. It is a complex syndrome with diverse underlying causes.

Further readings

- Atanda AT, Olowu WA. “Acute kidney injury in Nigeria: Review of a developing country’s perspective.” Pan Afr Med J. 2017.

- Esezobor CI, Ladapo TA, Lesi FE. “Paediatric acute kidney injury in an African setting: prevalence, outcomes and predictors of mortality.” BMC Nephrol. 2014.

- Ibrahim OR, Adamu B, Abdu A. “Acute kidney injury and associated factors in children hospitalized in a tertiary institution in Nigeria.” Niger Med J. 2016.

- Bellomo, R., Kellum, J. A., & Ronco, C. (2012). Acute kidney injury. The Lancet, 380(9843), 756-766.

- KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney International Supplements, 2(1), 1-138.

- Chertow, G. M., Burdick, E., Honour, M., Bonventre, J. V., & Bates, D. W. (2005). Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 16(11), 3365-3370.

- Mehta, R. L., Kellum, J. A., Shah, S. V., Molitoris, B. A., Ronco, C., Warnock, D. G., & Levin, A. (2007). Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Critical Care, 11(2), R31.

- Palevsky, P. M., Liu, K. D., & Brophy, P. D. (2013). KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 61(5), 649-672.

- Hoste, E. A. J., Bagshaw, S. M., Bellomo, R., Cely, C. M., Colman, R., Cruz, D. N., … & Kellum, J. A. (2015). Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Medicine, 41(8), 1411-1423.

Advertisement